|

| Old Schoolhouse Martinhoe

Writing Women on the Devon Land

A-Z of Devon Women Writers & Places

Marking the Way to Martinhoe

|

|

| Old Schoolhouse Martinhoe |

I began the journey toward writing a book about women many years ago, long before I researched then embarked on the written study of particular women writers. During the late eighties and early nineties, whilst researching and writing up my PhD, I ventured up to the remoter landscape north of the county to find where author/poet H.D.’s once stayed, in north Devon. She was there For several months in 196, during World War One she lived at Martinhoe then along the road at Parracombe. Just as many other women writers associated with the South West, H.D. had significant connections with at least two of its counties, in her case it was with three (Devon, Cornwall and Dorset).

What fascinates me about writers whose lives and texts cross county boundaries is the way their experience feeds into a kind of communication with the land space on which they writers lived and wrote, the way it affected their individual and combined selves and the ways in which their textual, literary roots also branch out and extend far beyond the surface, creating and recreating an endless kaleidoscope of inter/intra personal intertextuality.

Born in the U.S., H.D. (Hilda Doolittle), but much of her life and writing was influenced by our South Western shores and coasts. Without her presence I would not be here writing at all.

|

| Woodland Cottage Parracombe |

However I will pop in some extracts from a chronology, which details some of the events of the writer's Devon stay. If you want to read more it is taken from Louis Silverstein's H.D. Chronology Part Two 1915-March 1919:

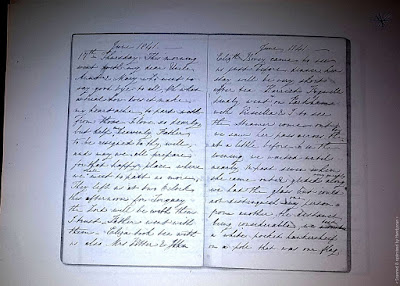

1916 February 22. HD. at The Schoolhouse, Martinhoe, Parracombe, North Devon

writes to Amy Lowell, her book [SEA GARDEN] has been accepted by Constable but will not come out in three months as she had hoped because of paper shortage; tells Lowell that she IS m Devon; discusses poems [Fnedman notes: not seen by LHS (H D. to Amy Lowell, [unpuL letter],

1916 February 24. HD. writes to George Plank; gives new address on envelope: "New address / c/o Mrs Dellbridge / Martinhoe / Parracombe / N. Devon"; says "some of us, no doubt all will turn up Isola Bella on Friday"; sets tune for 7:30; continues "we must be back early as we take mornmg tram' We are movmg our furniture to 44 Mecklenburg Square Fnday PM. Indicates that dinner will include herself, Aldington and John Cournos and perhaps F.S. Flint as they had asked 111m to dme With them that evenmg--they had planned a tea on Monday [for Plank and the wnutalls?] but it has all gone mentions confusion [LHS note: from this letter It seems as If the decrston to move to 44 Mecklenburg Square was a hurrted one]; mststs that dinner must be Dutch—says " we can't ask Flint otherwise & we can't impose on you forever and ever" (HD. to GP, [unpubl. letter]).

1916 March 6. HD. at Woodland Cottage. Martmhoe. Parracombe. North Devon writes to Harriet Monroe (Zllboorg notes).

1916 March 22 (?). HD. in Devonshire: writes to F.S. Flint: describes wanting actX1ttes and domestic life: says they are on their own trout stream (called the Heddon): the place is charming but there is only enough room for them and John Cournos (If he comes): speculates that Pound had expected to get Aldmgton's post on THE EGOIST had writtten a "charmmg Macheavelhan [SIC] note" to them which theyhad not answered: refers to widening gulf with Amy Lowell (HD. to F.S. Flmt.

1916 March 27. HD. at Woodland Cottage, Martinhoe. Parracombe. North Devon: Richard Aldmgton writes to F S. Flint and comments on her erotic attraction and his desire to sleep with her (Zilboorg introd. [draft)). Richard Aldington writes to Amy Lowell giving above address (Zilboorg notes: Houghton)

And here is a few extracts taken from a piece written about the journey I took with a friend some years ago down to the far west of Cornwall, on a follow-up quest to Martinhoe, to find the location of the poet's stay there, a couple of years after her trip to Devon ...

.... This has to be near Lyonesse’, I remind myself, echoing H.D.’s own description some (clock-time) 70 years ago. Sun-slant time is low behind this haze of mist, which envelops us, just as it does twenty clock years later, up on the wild north Devon coast reaches, when I am try to locate H.D.’s temporary home, near Martinhoe.

Today we’ve been driving along the snake-like, zigzagging B3306, between Zennor and Cape Cornwall. My friend finds this place creepy and would, I suspect, be content to turn around and make tracks homewards. I decide not to tell her about Alistair Crowley, about witches and other slightly sinister past inhabitants and goings-on in the area. All she knows, after I told her during the journey down from Devon, is that for a while during, World War One, D.H Lawrence lived not far away from here, up at Zennor, and that in 1918, H.D., the poet, (who was a friend of Lawrence) also spent some time (clock) somewhere round here; that she came away from the war turbulence of London to ‘accompany’ the composer Cecil Gray at the house he had rented (with Lawrence’s guidance) near, or at Bosigran; that she first met her lifelong lover/companion Bryher here, when H.D. invited her for tea; that she became pregnant here; that the pregnancy had had a negative impact on her already threatened marriage to Richard Aldington; that whilst here she worked on several significant texts, including the roman-a-clef Bid Me To Live; A Madrigal.[1]

My friend knows that, for both personal and academic reasons I wish to find the place where H.D. stayed. I want to feel the impact of this moor and sea-scape that forms the west Penwith peninsula, to let it inhabit me, as it had then possessed H.D.

I feel a stranger, an impostor. Traditionally, Cornwall, not Devon, is known as the Celtic land. And yet, the spiritual atmospherics of this part of Cornwall correspond with and complement that elemental landscape in north Devon, further east along the coast, which is also associated with writer H.D. For me, this landscape also resonates with that of Devon’s central mid-Devon region set between the two moorland plateaux, with its subliminal sacred-roots. I can imagine how extended and underground labyrinthine root systems which some call ley-lines, might travel through and along the line of the counties, beneath the palimpsest layers of their mutual prehistory, under the ancient field systems, the archaeological strata, the high moorlands. I understand my home county as a distinct entity, but also view it as part of a more extensive tract of land, which is defined by its common geological, historical, anthropological and social histories.

I shall absorb the mystic, mysterious aura of the peninsula's territory so as to bind me back into the atmosphere of her book, which, in turn will open perceptions toward re-membering the writer's time/thyme here, in 1918. For, it was H.D.’s affinity with this west Cornwall landscape that prompted my own preoccupation with landscape and text. After serendipitously coming across her writings one day, I began to understand the magical sacred appeal of my child-landscape with fresh eyes and to see why the location of my roots had such an emotional pull. In turn, that enabled me to explore the implications, both for self-identity and for my own writing.

That’s why I’m here; I want to breathe in this Penwith air, absorb the intoxicating essence blend of place and poem, the mix of panorama and prose; read the elaborate script set in the exquisite scene:

‘The jagged line of cliff, the minute indentations, the blue water that moved far below, soundless from the height, were part of her.[2}

....We stop in this car-space beside the old mine-shaft by the road, and after a sip of coffee begin to make our way along the tinners' tracks, which define this strip of coast land reaching out onto the cliffs. Walking along the edge of exhilarating South Western coasts, we should soon be able to see beyond these cliff-paths. But, though seemingly guided by unseen presences, we can not see far A fog-horn's booming in the seaward direction and disembodied voices whisper to us, stealthily as the mist. We do not know the language, yet can follow the trail of hieroglyphs seaward/sea/w/ree/a/ds.

Though

mystified, we know which track-fork to take when it splits, as it seems to,

every few yards. Hiss-hiss. Here-here.

Hiss-hiss. Mist here must represent the spirit/s of the place, I think. And,

we have been travelling along the snake-road, genius-loci of Cornwall’s most

sacred space. I do not feel threatened by stories of this area as an oppressive

‘spiritual black country’. On the contrary, the mist wraps itself comfortably

around us and as we saunter across the grassy sward tracks, begins to trail

into ribbons and then to lift, to disperse, so that by the time we reach what

is left of the fortifications of Bosigran Castle, the sun is hovering over the

Atlantic spread below us. Other than the springy, tangy and lightly scrubby

heath at our feet, which is stippled with tiny violets, we are cocooned in a

blue shroud. A heaven of Cornish seas; the bliss of springtime South Western

skies.

My

friend, sun-worshipper, wants immediately to bathe in one of the ‘room’

enclosures that are formed between the castle’s esoteric relics. I wonder if

H.D. had occasion to do the same, to remove her garments and lie out in the sun

when she visited the ruins. But then, I also wonder if, when she was here, the

stone walls of this place were, at least to some degree, still intact. A lot can

change in clock-time over seventy years. In its hey-day Bosigran must have been

a massive and magnificent castle; it ran across the neck of the headland and

may have been a ceremonial site. I remind myself to look out my copy of Bid Me to Live when I get home, so that

I can re-visit the place as though from H.D.’s eyes, follow the footsteps of

the poet as she trailed around the paths of this coastline.

It

is whilst we are doing a recce of the castle that we hear the knockings. They

are loud and are echoing over from the next hill of this broken line of

headlands that culminates at Cape Cornwall. Instantly, I remember that Cecil

Gray – and possibly H.D. herself - spoke of experiencing these phenomena and

that the knockings were rumoured to be the ghostly after-echoes of tin miners

quarrying in the locality. My friend shrugs, grimaces. I do not know what to

think. Although this region is known for its mystical goings-on, both

historically, and now, I am not really a believer in ghosts; just interested in

the enigmatic possibilities of mysterious cryptic occurrences, which could as

easily be interpreted in psychological as in psychic terms. But those knockings

are for real; we both hear them. I allow them to melt and merge as soundscape

to accompany the inner map of H.D. in Cornwall beginning to form in my mind.

Next

question is, where did she stay? Where was this large house that was called

‘Bosigran Castle’ or, in H.D.’s novel BidMe to Live, ‘Rosigran’? Was it purposely named after this ancient ruined castle?[3] We venture down other tracks looking to find the site where a once ‘sizeable’ cottage may have been, may still be. But there are no buildings here and no evidence of any. We realise

that we may not be at the exact location, that the site may be a little to the

north east and that the house's name may have confused us. Did H.D.'s then

lover Cecil Gray and his companions want their friends to think they were living

in the castle? It’s also possible that the house may have gone, some years ago.

Today

we have no more time to explore. We will return. H.D’s words buzz around my head:

I suppose we will come back ... I will never see you again ... I will go on scribbling.’[4]

I shall return to H.D’s South Western

sea lands; even if I have to cover, or cross, the same ground.

It seems as though yesterday, though in clock-time is a long time.

In clock-time it’s a long-time; it still seems as though yesterday.[5]

In clock-time it’s a long-time; it still seems as though yesterday.[5]

There is also a sequence of my poems written in commemoration of H.D.'s time in Devon published in Shearsman Magazine 111/112: see a few extracts below.

Shearsman 111/112

Driftwood

Breathless,

at last we are here,

at the sea-shrine,

though few seem to venture to this abandoned plot,

where at the time of the latest tide

a twist of drift left

behind figures

for us,

the gravitational curve,

a centenary - the sea's-time.

'you are useless, O grave, O beautiful' (H.D. 'The Shrine')

........

We arrive from the old Roman carriageway

high

above the sea, next the sky,

way below

in coastal chasms, white against white

gannets and gulls

beating,

breaking surf -

at home

our multimedia screens still on

flashing in-perpetuum into our comfort-zone rooms,

every opportunity, we whip out phones from pockets or bags,

photos flash,

burst from our finger-tips -

we remain alive with interactive possibility,

yet find it impossible to conjure a picture from the swiftly lit

spark of a stated fact.

Here only flashes, a series of dots and dashes

cracking along faults of the rocky screes on this north Devon coast

from long-ago beacon fires

intended for those, rudderless,

tossed in the turbulent sea,

waiting,

in the Channel,

watching for life or death landings.

'I have stood on your portal/and I know-/you are further than this, still further on another cliff'

(H.D. 'Cliff-Temple')

1. In which the name of the heroine, Julia Ashton, an avatar of H.D. herself, always seemed to me to be a close sound-echo of my own name. H.D’s writing sound-effect, or phonotext, is always significant, so this closeness had hooked me into the book.

2. From H.D., Bid Me to Live; A Madrigal.

3. Returning from her solitary walk along the cliff tracks, H.D./Julia in Bid Me To Live, briefly describes the house as it ‘loomed suddenly like a greyship, rising from the sea’ and someone noted it was a ‘big lonely house on the edge on the wildest part of the coast ... with seven rooms and a great view out towards the Scilly Islands out the front’ and that it was ‘near Gurnard’s Head’ (Mark Kinkead-Weekes, D.H. Lawrence Triumph to Exile, vol. 2, 1912-22; The Cambridge Biography of D.H.Lawrence (Cambridge University Press, 2011). Interestingly, H.D. did not refer to the castle itself in her book, which seems strange, given its size and historical importance.

4. Bid Me to Live. I have been down to Penwith several times since, including once with participants of the ‘H.D reading party’, in the early 1990’s, when a group of us manoeuvred the lanes and byways from Trevone Bay toward Cape Cornwall. Again, not one of us could work out where the house in which H.D. lived for several months was sited. I remember some heated discussion; but eventually we gave up our search in return for the delights of a local Cornish cream tea.

5. H.D.

2. From H.D., Bid Me to Live; A Madrigal.

3. Returning from her solitary walk along the cliff tracks, H.D./Julia in Bid Me To Live, briefly describes the house as it ‘loomed suddenly like a greyship, rising from the sea’ and someone noted it was a ‘big lonely house on the edge on the wildest part of the coast ... with seven rooms and a great view out towards the Scilly Islands out the front’ and that it was ‘near Gurnard’s Head’ (Mark Kinkead-Weekes, D.H. Lawrence Triumph to Exile, vol. 2, 1912-22; The Cambridge Biography of D.H.Lawrence (Cambridge University Press, 2011). Interestingly, H.D. did not refer to the castle itself in her book, which seems strange, given its size and historical importance.

4. Bid Me to Live. I have been down to Penwith several times since, including once with participants of the ‘H.D reading party’, in the early 1990’s, when a group of us manoeuvred the lanes and byways from Trevone Bay toward Cape Cornwall. Again, not one of us could work out where the house in which H.D. lived for several months was sited. I remember some heated discussion; but eventually we gave up our search in return for the delights of a local Cornish cream tea.

5. H.D.