Toward the Lodestone; longing for the Devon moors

(an excerpt)

... It's mid C18, child

Charlotte Yonge, future-to-be writer, riding down from the Dartmoor slopes with her family in a horse-drawn carriage, is drawing nearer a beloved holiday destination on the under-moor slopes below:

We used to go every autumn, all but grandmamma, in the chariot with post-horses, sleeping either one or two nights on the road … At last we turned down Sheepstor hill and while dragging down the steepest part over the low wall came the square house, in sight if we came by day, or if late, the lights glancing in the windows. (

Charlotte Mary Yonge; her Life and Letters (Palala Press, 2016).

As I imagine her, with the carriage dipped and swayed in the rugged tracks toward

Puslinch, near Yealmpton, in the South Hams, the young novelist was inwardly manoeuvring a sense of twists in life-narrative tales to come.

|

| Puslinch |

Already, searching for the elusive epiphany or climatic moment, perhaps Charlotte suddenly glimpsed her inner vista through a gap in the hedge, then a gate and noted how her vision was reflected by the outer scene. That shock of the scene now spread before her mirrored that of the inner scenic-icon; there was a place in the interior mind’s clearing.

Yonge was evidently entranced during those visits to her Devonshire cousins, at Puslinch, where she went with her parents to visit her large family of Devonshire cousins.

Later, when drafting one of her first novels, Yonge relived that moment when she spotted her beloved

Puslinch. Again and again, during her long writing career the author's beloved cousins' home became the locus of Charlotte Yonge’s future ideal of place, the location where she imagined the setting for her characters' experiences.

In

Pillars of the House, for instance, a young girl called Geraldine 'was in a quiet trance of delight’. Staying with the noisy, beloved cousins,

.she had first found a chink in the awning, but had watched with avid eyes the moving panorama of houses, gardens, tress, flowers, carriages, horses, passengers, nursemaids, perambulators, and children … there were greater delights; corn-fields touched with amber, woods sloping up hills, deep lanes edged with luxuriant ferns, greenery that drove the young folk half mad with delight … the children began to rush and roll in wild delight on the grassy slope, and to fill their hands with the heather and ling, shrieking with delight. Wilmet had enough to do to watch over Angela in her toppling, tumbling felicity; while Felix, weighted with Robina on his back, Edgar, Fulbert, Clement, and Lance, ran in and out among the turf'.

If you're unfamiliar with Yonge's fiction, but like me, come across one of her many novels in a second hand bookshop, or on the web, skimming through its pages you'll quickly have the impression of a fleet of children; they whoop and scamper through rose-laden arbours of gorgeous gardens and inside houses with Georgian marbled fireplaced rooms.

Yonge’s fictional worlds re-envisioned the Devonian territories of those childhood holidays and her characters sprang directly from her 'cousinland', the extended fellowship of boisterous cousins, with whom every holiday she spent 'rapturous days' below the southern slopes of Dartmoor, where the

river Yealm rises on

Stall Moor. Her cousins took the young writer with them on their excursions to local places of interest, including

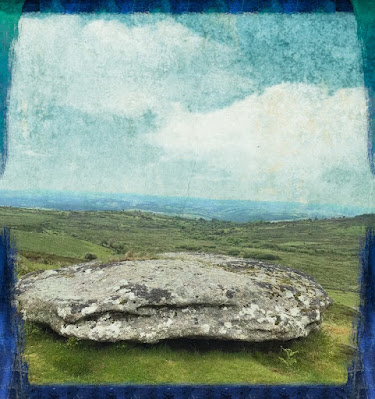

Kitley Point and the Yealm ravine. On one such visit the party picknicked ‘at a curious place formed by grass and rocks on the banks of the Yealm’ and on another outing, near a precipice above the hamlet of Torre, the ecstatic Charlotte viewed ‘the ravine which opened on the wild moor, scattered with rocks and giving a sense of mountain freedom’.

Charlotte Yonge wasn't alone in her addiction to Devon moorland's border country. Moor is a lodestone for many who live, stay or as exiles, used to live, in Devon; it lures us; for Dartmoor's tors are visible from most of its bordering lowlands. When we return from foreign lands we scroll the horizon we looking urgently for its undulating peaks and troughs; its curves and tors can be viewed from almost every direction. Spotting a spectacular moor view between a filter of green leaves in the high hedge on the green-lane we catch breath.

Over the years many moor loving writers have lived beneath the distinct tors within the green-laned foothills; their vista to moor scapes may be blocked; but a glance through a tree-fork or over a bank might reveal that frisson of 'moor'. Many authors living, or like her, staying for holidays at a site somewhere along the laced viewing-path across to Dartmoor were affected by the outlying prospect of blue-layered undulating tors. For example (as I've noted already in previous posts), although

Jean Rhys’ famous

Wide Sargasso Sea is not located in England’s Westcountry - and the novelist was reputedly hostile to her local Devon surroundings - Rhys’ introjections of distant Dartmoor's wave-like curves from her cottage in

Cheriton Fitzpaine may have impacted on her novel:

We pulled up and looked at the hills the mountains and the blue-green sea. There was a soft warm wind blowing but I understood why the porter had called it a wild place. Not only wild but menacing. Those hills would close in on you. (Wide Sargasso Sea)

Similarly, looming moor influenced Sylvia Plath’s poetry written in the foothills, at North Tawton. Dartmoor's ridge of tors seen from the town are an implicit transposed backdrop, a ‘blue distance’ in some of the poet's later poems, including ‘Sheep in Fog’, ‘Ariel’ and ‘Winter Trees’:

Stasis in darkness.

Then the substanceless blue

Pour of tor and distances.

(Sylvia Plath, '

Ariel),

Turning the moorland tables, if you look back from the summits of Dartmoor, you can see across to the north moors of Devon. And vice versa. This fact has proved useful for several women authors. In the mid 1960s,

Doris Lessing, who at the time was living in the Dartmoor village of Belstone, and there drafted several novels (see

Celebrations), in the converted shippen of her longhouse; (part of which I believe is now a holiday cottage - see

here).

I read somewhere that Lessing once commented that this room's large picture window enjoyed panoramic views across the paddock, not toward the high moor, but further away, into the distant northern vista, of Exmoor.

Then there was

Sylvia Townsend Warner, who found she could easily manipulate her readers via swopping Devon's moorland scapes in their minds. Warner's stories don't always match background scenery with real place. For instance, the story ‘A View of Exmoor’ was originally titled ‘A View of Dartmoor’, but apparently, after the publisher informed her that many people associated ‘Dartmoor’ with ‘prison’, Warner promptly swapped titles and places. Scenic features in the stories were less than precisely identified, there were, ‘ten foot hedges’ and ‘a falling meadow, a pillowy middle distance of woodland and beyond that, pure and cold and unimpassioned, the silhouette of the moor’ (See in

Sylvia Townsend Warner,

Selected Stories (Hachett, 2011. When put alongside the other defining feature the ‘moor mist’ is actually more suggestive of Dartmoor, but still, presumably, Warner's readers were satisfied that the 'view' in question matched with Exmoor).

Although the time is slightly out of the remit of my blog, in the later decades of the C20 Penelope Fitzgerald, visiting her daughter at Milton Abbott in the 1990's, commented on her enchantment with Dartmoor's edging southern slopes:

Turn left at Mary Tavy … Between Mary Tavy and Peter Tavy … there is a track leading down through oak trees to a bridge across the Tavy … You can sit here by the golden-brown water, watching it divide round the granite rocks in its bed, or you can paddle or go a little way across on the stepping-stones. There is no particular need to cross the bridge. This must be one of Devonshire’s most undemanding expeditions, but it’s the one I remember most clearly of all, between summer and summer.('Writer's Britain; Spirit of the Moors', in The Independent, 20th February, 1994).

It's as though Fitzgerald’s moorland river-haven connotes an indeterminate place between one world and the next, a site where one can dream one’s interior worlds into being. It is a frontier essential to the writer, who, forgetting, digging deep and putting her own real life on hold, sinks into an imaginary place; she's conjuring a series of signs set in process by the zone of reflection on the bridge over the water that she doesn’t have to cross. Writer/initiate, is at the place where two inner waters meet: that of Lethe, (forgetfulness of the past) and that of Mnemosyne, (memory, the mother of the muses): the kind of memory that gives birth to text.

Just as Penelope Fitzgerald demurred, on the bridge of stepping stones on the edge of Dartmoor, earlier women visitor writers to Devon's liminal landscapes also lingered, gossiped, reflected and mused, while rambling through its labyrinthine lacings of ancient and high-hedged lanes. For some, the scene was transformative, taking them down other avenues into the exploration of new genres of writing; sometimes a location inspired the enchantment of a novel or story. Others fell into the spell of the place and then refigured its focal characteristics into compelling fiction. Ritual submersion in the territory heightened the writer’s perceptual awareness; induced intoxication...

No comments:

Post a Comment

Comments welcome!