Finding a Forgotten Devon Author's Grandmother; Who was Edith Dart’s Granny Jane Sampson?

|

| Lanes, distant moor and ‘Lydcott’, a farm (once home of my mother Clarice Green Sampson) in area of South Tawton, Taw Green & Sampford Courtenay |

|

| Cover of PlayBook Sareel |

Writing the Devon Rural

It was a long low house, with whitewashed cob walls and a thatched roof, cowering underneath the shelter of a tor, with only a little patch of garden ground, roughly fenced in, separating it from the open land that stretched away from it on either side. On one hand there was cultivated land that had been snatched from the jealous moor in other days, when public rights were less authoritative than at present; but it was a small portion only, kept from returning to its wild state by constant toil and unremitting efforts. The granite boulders pushed through the surface everywhere, the garden was no more than a handful of earth above it, where only hardy plants and a few straggling bushes might survive (From Sareel, Edith Dart)The vivid description of a farmhouse on the edge of Dartmoor comes from Sareel, a novel by Edith Dart, published circa 1920.

As I’ve already noted in earlier posts about this almost forgotten Devon author, as yet Sareel is the only one of her several novels I’ve been able to read. (You can read the novel on Samsung Play Books). Like the fiction of Dart’s close friend MP Willcocks, this story and I’m assuming most, if not all, of Dart’s other novels, Sareel is well and truly bedded down in and around the moorland landscape which, rimming the northern horizon of her Crediton home, must have been a formative influence and inspirational force for the young writer, and then later, a potent location providing a never-ending physical and sensory descriptive backdrop for the gentle romance tale featuring her young fictional heroine.

|

| Views of Dartmoor ridge from places near South Tawton/ Sampford Courtenay/and Taw Green |

The farmhouse where young orphan Sareel is driven as she leaves her orphanage home is located on moorland’s liminal edges, a place which had ‘only a little patch of garden ground, roughly fenced in, separating it from the open land that stretched away from it on either side’.

Edith may have been influenced by her friend MP Willcocks, whose family having been yeomen farmers in Devon for generations, showed personal knowledge of farming life in her novels - and although their names are often changed or swapped for one another’s, people and places in her fiction appear to be directly taken from real people and places in her Devon rooted life. For example, in her first novel Widdicombe the places and characters are very much fictional transformations of moorland or parishes near her home at Ivybridge.

Common Names

I went off on a genealogical diversion. Although others had already researched Edith’s immediate family these studies didn’t seem to trace her Sampson grandmother branch.

William Dart’s mother Jane

So we begin with William Dart, Edith the author’s father, a local builder from Crediton, born in 1833 who was son of John Dart, born in 1792, who had married Jane Sampson. As noted above, Jane and John, along with their son William, aged 16, ‘builders apprentice’ are named on the 1851 census; Jane, 61, is three years older than her husband. The 1841 census ten years before has the couple, now both apparently the same age (45), with five children – the I believe youngest sibling William (Edith the author’s father) is eight. In other words there appears to be some discrepancy in facts about Jane’s age.

As I said I’d already done a bit of digging and had a bit of a hunch that rather than being born in Crediton where she spent her married life, Jane may have come from a branch of the Sampson family who for several generations had rooted in the parish of South Tawton just east of Okehampton. So it was with some satisfaction that I came upon a Dart family tree naming Jane and laying out a retreating trail of South Tawton Sampsons. And, oh brilliant (!) the extending familial surnames tree took in those who also pop up in our family line – including Lang; Gregory; Paddon; I felt I might be getting closer!

Another passage near Sareel’s opening evokes a farmhouse kitchen:

She went down to the great stone - paved kitchen, with its huge open fire - place and fire of logs on the hearth , above which hung on chains great pots and kettles that she was soon to find very heavy to move and fill. There was a black oak dresser, laden with crockery and winking brass candlesticks, and huge cupboards let into the wall on two sides of the room . Sareel wondered timidly if she would ever get to learn where everything was kept.

Reading the novel I began to wonder Edith where gained her inspiration for her fiction’s backdrops; was she just drawing on her own imagination, or more likely, from her own observations of the landscapes with which she must have been familiar from jaunts out and about on and near the moor? Or, could she perhaps have had more specific locations in mind, taken from places she herself knew, or knew of, through her parents’ tales about them? Fiction of this time set in rural Devon locations by women authors is rare (at least in terms of the writers we know about; there were more female novelists out there, but they and their books have long been forgotten). Speaking from the point of view of a reader who has memories of several farming places it’s a revelation for me to be able to read novels written by Devon women about individuals from the past whose backgrounds are similarly countrified.

Edith may have been influenced by her friend MP Willcocks, whose family having been yeomen farmers in Devon for generations, showed personal knowledge of farming life in her novels - and although their names are often changed or swapped for one another’s, people and places in her fiction appear to be directly taken from real people and places in her Devon rooted life. For example, in her first novel Widdicombe the places and characters are very much fictional transformations of moorland or parishes near her home at Ivybridge.

Common Names

I was thinking about the fictional Devon based scenes-capes conjured by Edith Dart whilst whiling away a few hours delving into one branch of the author’s paternal ancestry. My interest was partly because as literary researcher there is often fascination with the background life of the subject, including an understanding of the writer’s family. And in Edith’s case my academic motivation was also promoted by a more personal curiosity. When I first posted about Edith I was intrigued to find that we shared a grandmother’s name: her paternal grandmother was called Jane Sampson; my paternal grandmother was identically named Jane Sampson. Could there be an ancestral link? Could the two Janes be connected? Did Edith’s and my family have a close link? The latter possibility was soon put aside. Edith’s Jane and my Jane; no not related: our family’s Jane Sampson was actually her married name; whereas Edith’s Jane Sampson, her father William Dart’s mother, was her maiden name.

How many generations back?

But for centuries back my/our Sampson family has been deeply rooted in the parishes of mid – north Devon, and given that Crediton was Edith’s home town, it seemed logical that her father’s Sampson ancestors may have also sprung from these parts; so it’s feasible the two family clusters are connected. But, if so, how? And when? Luckily, as hundreds of other people with access to the brilliant various online genealogical tools, I’ve already spent hours and hours tracing my father’s paternal predecessors. Although there are still many gaps in our Sampson genealogy, one side of this genealogical puzzle was semi-half complete.

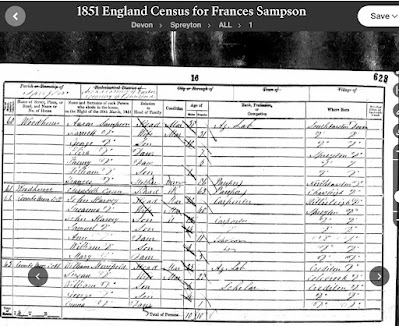

Amateur genealogists love any excuse to loiter in the shadows of genealogy so I began to delve into Edith’s ancestry, looking into the immediate paternal branch of her father’s mother. Who was Edith’s Jane Sampson? Where was she born? There were clues… On the census of 1851 Jane is listed living in Crediton along with her husband, Edith’s grandfather John Dart.

Amateur genealogists love any excuse to loiter in the shadows of genealogy so I began to delve into Edith’s ancestry, looking into the immediate paternal branch of her father’s mother. Who was Edith’s Jane Sampson? Where was she born? There were clues… On the census of 1851 Jane is listed living in Crediton along with her husband, Edith’s grandfather John Dart.

|

| Census 1851 Crediton showing Jane Dart (Sampson) |

The couple had married in 1814. According to the census, like John, his wife was from Crediton. However experience has taught me that the given matching of name and place of origin on a census is not necessarily proof of anything, especially of place of birth or baptism. I needed to widen the exploratory net. Was Edith’s Jane Sampson really from Crediton?

I went off on a genealogical diversion. Although others had already researched Edith’s immediate family these studies didn’t seem to trace her Sampson grandmother branch.

But when I logged into Ancestry and browsed through related family trees it was soon clear that I was mistaken; several others have already researched Edith Dart’s Sampson branch. Thus, here, to some degree I’m indebted to and repeating what I’ve found on those trees; where and when possible (because trees on Ancestry need to be checked as there are often notorious errors) I’ve endeavoured to verify the facts. It’s not always possible though, as frequently with the large families in the rural communities of C18/19 Devon there are complex multiple instances of children with the same name; ie first/second cousins and it’s not simple to work out which branch of the family the individual is from; sometimes indeed it’s impossible.

For this study I’m also indebted to another literary member of the Devon Sampson family. Fay Sampson has meticulously traced her own Sampsons and has constructed a brilliant website about them.. It is her investigation into the earliest of her own Devon Sampsons back in the vicinity of Winkleigh that has enabled me to hazard a guess about one possible ancestor from whom I think logically all these other Sampsons may have sprung. Of that more later…

|

| Trees just east of Winkleigh looking over to Dartmoor |

William Dart’s mother Jane

So we begin with William Dart, Edith the author’s father, a local builder from Crediton, born in 1833 who was son of John Dart, born in 1792, who had married Jane Sampson. As noted above, Jane and John, along with their son William, aged 16, ‘builders apprentice’ are named on the 1851 census; Jane, 61, is three years older than her husband. The 1841 census ten years before has the couple, now both apparently the same age (45), with five children – the I believe youngest sibling William (Edith the author’s father) is eight. In other words there appears to be some discrepancy in facts about Jane’s age.

As I said I’d already done a bit of digging and had a bit of a hunch that rather than being born in Crediton where she spent her married life, Jane may have come from a branch of the Sampson family who for several generations had rooted in the parish of South Tawton just east of Okehampton. So it was with some satisfaction that I came upon a Dart family tree naming Jane and laying out a retreating trail of South Tawton Sampsons. And, oh brilliant (!) the extending familial surnames tree took in those who also pop up in our family line – including Lang; Gregory; Paddon; I felt I might be getting closer!

|

| South Tawton Church & Church House |

There were a few other possible Janes, but the folks on Ancestry trees seemed mostly in agreement. And after a bit more exploration the tree seemed to make a lot of sense. Daughter of William and Frances Sampson (nee Gregory, baptised in North Tawton), Jane was baptised in South Tawton in 1789, second eldest child of a large family. The siblings are all recorded: Robert (1785); Jane (1789); Mary (1791); John (1794); Oliver (1796); Fanny (1800); William (1893); Elizabeth (1806); Caleb (1809); Aaron (1812); and Maria.

Who were they? Where?

First I want to establish the basic line of what I believe to be the kin-connection between Edith Dart’s Sampson branch and our Sampson branch; in those days the latter were well and truly established yeoman farmers in nearby Broadwoodkelly. I’d followed the male line back to the end of the C17 and there’s evidence they were in the parish and nearby other parishes centuries before this.

Fay surmises that her own forefather, John Sampson (who I believe may be from the same branch as that of Jane Sampson, our erstwhile Edith’s grandmother) – and for whom there seem to be no other recorded baptisms - most likely was a son of this Edmund:

Anyway, here we can catch up with John Sampson, probable son of Edmund of Broadwoodkelly (forefather of Fay Sampson and Edith Dart’s grandmother Jane Sampson). This John married Grace Paddon. They were parents of five children including the Caleb Sampson listed above. Thus the line from which our Crediton author Edith probably stems descends from John through Caleb Sampson (his wife ‘Elizabeth’); William Sampson (and his wife Jane Lang); William Sampson (and wife Frances Gregory); Jane Sampson (and her husband John Dart). William Dart Edith’s father, is John’s son.

Broadwoodkelly and Beyond: South Tawton: North Tawton

For several centuries the Sampson family branch from which Edith’s grandmother Jane came were based in South Tawton, a large parish tucked into the edges of the northern moorland folds.

A couple of archival documents and censuses suggest possible homes and occupations, allowing us glimpses into fragments of the South Tawton Sampson family’s lives. For example, we can work out a little about the lives of William and Frances Sampson and their children. The family seem to have very evident traces in South Tawton during the late C18 and early C19. It might be this William Sampson who took a Mary Gregory as apprentice in 1785. Was he a yeoman in the parish, as were his distant cousins back in Broadwoodkelly where his ancestors were from? Was Mary a close relation of his wife Frances? Perhaps sister, or niece? Land Apportionments for 1847 for South Tawton show a Robert Sampson occupier of a house and garden in the parish; he could be Robert, William and Frances’ eldest son and eldest brother of Jane, Edith Dart’s grandmother. Similarly, an Oliver Sampson rents house and garden at a hamlet of South Tawton called Ramsley and is also renting other property and or land, a garden at Burgoins and four acres at Town Barton and another plot at Holmeses. Oliver also has part share of a couple of plots with another man called George Westaway. Oliver is probably another, younger son of William and Frances, born in 1796. A Mary Sampson is named on the land census as tenant at the large and probably ancient farm at Cesslands. She may be another daughter of the family, or more likely, a widow of one of the sons. Turning to A2A Discovery: an abstract of a Will in 1807 for Caleb Sampson (Cessland/Sessland), may be that of the same William Sampson’s uncle, who was born in 1736. He must be the same Caleb of Sessland, who takes in Samuel Gillard a ten year old apprentice in 1841; a number of other apprentices are taken by Caleb in the years running from circa 1830-up to 1841. I’m tentatively suggesting that an earlier generation of the family – possibly beginning with the Caleb Sampson who seemingly moved over to the parish from Winkleigh (marrying a mysterious ‘Elizabeth’ whose surname as yet is not known) - took over Sessland after this marriage. Possibly earlier generations of the family were farming there. These references taken together suggest that, as with the Sampson kin over at Broadwoodkelly, many of the South Tawton Sampsons were more than likely farming.

Frances; a Devon author’s Great Grandmother

I've not yet had a chance to find out about Frances Gregory's family back in North Tawton where she was baptised. Gregory is a well-known longstanding North Tawton name and the family have for generations intermarried with branches of the Sampson family. I've concentrated on exploring Frances' life as mother following her marriage. In 1851 Frances Sampson, who I believe was mother of Jane Sampson (Edith Dart’s great grandmother and grandmother respectively) aged 86 is living (or staying?) at ‘Woodhouse’ farm with one of her sons and his family. Her husband, William from the Sampson ancestral line, must already have died. Aaron Sampson is I believe Frances’ youngest son from her family of 10-11 siblings; 58 years old, he is named as agricultural labourer. Wife Harriet and 4 children are named along with Frances, now not only a widow, but rather sadly, also labelled as ‘pauper’.

Frances Sampson had probably lived with her youngest son Aaron for many years. She’s listed with his family ten years before, in the 1841 census; the family are at Higher Langabeer farm, a farm bordering Sampford Courtenay some six or seven miles west of Woodhouse.

75 years old, Frances is named with Aaron’s wife, and their son George. There’s also Maria (21), who people on ancestry usually record as Frances’ youngest daughter, but who realistically cannot have been; by 1820, Maria’s baptismal year, Frances would have been well over fifty! I believe Maria must be illegitimate daughter of Frances’s daughter who was also called Fanny. Perhaps her grandmother took the child in and brought her up… (Interestingly a census sample for 1851 records Fanny Sampson (Maria’s mother), as house servant at nearby Oxenham House). By the end of 1851 Frances, William’s widow, has died, presumably while she was with her family at Woodhouse. As mentioned above, she was born and married in nearby North Tawton (1765 and 1785 respectively) so had probably never moved far away from her childhood home. (And here, time allowing I’d love to go on another genealogical recce to explore the Gregory family descent, for our Broadwoodkelly Sampsons also interrelate with the family).

In 1841, Jane, Frances’s eldest daughter was, as I noted earlier in this piece, married and living in Crediton. Jane is about 45. The couple have five children: Samuel (20); James (15); Maria (13); Elizabeth (11) and William (who years later would be father of Edith Dart), their youngest, who is eight. Presumably, Jane, with William and some of his siblings would have travelled across from Crediton to the farmhouse over in the rural backwaters near Sampford Courtenay, to visit her mother and brother and family. Ten years later, in the early 1850s, journeys to visit Frances over at Woodhouse farm would have been shorter. By then William’s grandmother was nearing the end of her life; her youngest son and still living with his parents in 1851, William could easily have accompanied his mother as she spent time with his ailing grandmother back in South Tawton.

Finding the Farmhouses

As noted in Remembering Edith Dart Edith Dart’s immediate paternal family, especially her father William, were established and increasingly respected local builders; but her agricultural farming family legacy linked with her Sampson grandmother may have influenced her as writer when she was growing up, perhaps providing backdrops and backstories for the fictional characters she created. Although Edith’s grandmother on the Sampson side had died in 1865, several years before her youngest granddaughter’s birth in 1872, Edith’s older sisters must have known Jane as at the age of 72, in 1861, their grandmother was still living with her son and his young family in Fountain Court, Crediton. I guess there were cousins from the extended family still living in and around South Tawton who her father and his kin may have kept in touch with. I imagine that Edith Dart picked up the tales told her by her father about his visits to his grandmother’s home in the farmhouse back in South Tawton and he may also have related folk tales about forefathers and foremothers in the rural hideouts of the Devon villages, hamlets and farms lying under moor’s rim.

I know as poet sometimes I return to the tales told me about people in my parents’ families who I never had the chance to meet, including grandparents who’d died before I was born, and their parents. And amongst the vivid memories of special places in childhood we all carry mine include a farm house in the depths of mid Devon, where my own father Laurence Sampson loved to take us as he rekindled his own nostalgia for the place. The farm had a mixed effect on me. Dark and brooding and atmospheric, yet at the same time, its inhabitants, Dad’s first cousins, always gave us a warm welcome, and their Devon teas were to die for. The obligatory huge open fireplace pervaded the place, gave it its sense of unfathomable history; its evocative mystery. We were cocooned within the crocks and fire-irons around which we all sat brooding as our father and his cousins caught up with the latest 1950,’s farm gossip.

Coulson is situated between the villages of Winkleigh and Broadwoodkelly and is still as far I know a working farm. One of the many such inhabited by a long stream of Dad’s farming forefathers - where, back in the 1950’s, his cousins John and Henry and John’s wife Edie still farmed and where (though I wasn’t consciously aware of in those days), a tangled family network had previously unfolded.

But I must not let myself get carried away… I just wanted to explore how even the rustic nostalgia cast by a rural Devon family background can remain in one’s heart and pop up sometimes needing to be resurrected as fiction; or in my case, as poetry…

I can’t judge the literary quality of Edith Dart’s other novels for reasons I’ve already explained. I'd need to have a chance to read them, which I hope will happen one day. But isn’t it odd, isn’t there something amiss, when novels by male authors of her, or of her near contemporary local male writers, such as Eden Phillpotts are remembered, praised for the way they record and bring local characters and places to life and indeed, are still in print? For example see this link to an assessment of a novel based in South Zeal, the joining village to South Tawton (where Edith Dart’s Sampson ancestors were from), by the acclaimed Phillpotts:

Who were they? Where?

First I want to establish the basic line of what I believe to be the kin-connection between Edith Dart’s Sampson branch and our Sampson branch; in those days the latter were well and truly established yeoman farmers in nearby Broadwoodkelly. I’d followed the male line back to the end of the C17 and there’s evidence they were in the parish and nearby other parishes centuries before this.

The following will not be a definitive genealogy, far from it, the ancestral lines are too confusing and convoluted, with several possible divergent familial branches; but putting it out here may one day attract another Sampson historian; someone who can hopefully tease out the intricacies of the mid Devon rural genealogical mazes more than I’m able to.

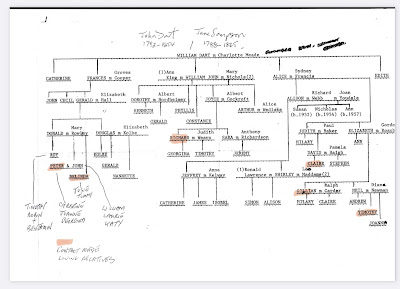

So here’s the outline of the Sanpson tree that descended to Jane Sampson of South Tawton as at the time of writing this it seems to recede:

Jane’s mother Frances’ husband William Sampson, also from South Tawton, was son of another William. It looks as if the elder William had moved over to South Tawton from Winkleigh.

William’s father Caleb Sampson’s parents were from nearby Broadwoodkelly, and that’s where our family’s Sampson branches, from whose descendants Edith’s and our Sampson clusters merge, may meet up. It’s a retreating line of approximately six generations.

The supposed common ancestor, two more generations back, an Edmund Sampson, born in 1615 (probably) son of another Edmund Sampson (possibly) married Dorothy Brocke, in Broadwoodkelly in 1644.

As Fay Sampson explains,

So here’s the outline of the Sanpson tree that descended to Jane Sampson of South Tawton as at the time of writing this it seems to recede:

Jane’s mother Frances’ husband William Sampson, also from South Tawton, was son of another William. It looks as if the elder William had moved over to South Tawton from Winkleigh.

William’s father Caleb Sampson’s parents were from nearby Broadwoodkelly, and that’s where our family’s Sampson branches, from whose descendants Edith’s and our Sampson clusters merge, may meet up. It’s a retreating line of approximately six generations.

The supposed common ancestor, two more generations back, an Edmund Sampson, born in 1615 (probably) son of another Edmund Sampson (possibly) married Dorothy Brocke, in Broadwoodkelly in 1644.

As Fay Sampson explains,

‘There are intermittent records there [in Broadwoodkelly] from 1609, which include the baptisms of Edmond, son of Edmond Sampson, in 1615, and George, son of Edmond Sampson, in 1620. Edmond senior died in 1626. There is then a gap in the baptismal register from 1635-54.’ (See Fay Sampson Family website).

Fay surmises that her own forefather, John Sampson (who I believe may be from the same branch as that of Jane Sampson, our erstwhile Edith’s grandmother) – and for whom there seem to be no other recorded baptisms - most likely was a son of this Edmund:

‘This includes the period around 1650 when we would expect John to be born. When the register recommences, there are baptisms for three children of Edmond Sampson, presumably the one born in 1615: Edmond 1655, Richard 1657, and Sarah 1660. It is likely there were more children born before them. From the late 1660s there are children for William Sampson, and in 1678 for Robert Sampson. Both of these could be older sons of Edmond, and it is possible that John was, too’. (Fay Sampson’s site)My supposition, similarly to Fay’s, is that our Sampson branch’s ancestor may well have been the Robert mentioned above, who could have been, like John, another son of Edmund; but like him, his record is missing in the Broadwoodkelly records gap. (It’s beyond the scope of this piece, but our Sampson branch in BWK comes to an abrupt halt with a Simon Sampson. I’ve spent years trying to establish Simon’s birth parents, and at present Robert seems the most likely candidate to be his father; BUT I am not certain and Sampson researchers out there might well prove me wrong!).

Anyway, here we can catch up with John Sampson, probable son of Edmund of Broadwoodkelly (forefather of Fay Sampson and Edith Dart’s grandmother Jane Sampson). This John married Grace Paddon. They were parents of five children including the Caleb Sampson listed above. Thus the line from which our Crediton author Edith probably stems descends from John through Caleb Sampson (his wife ‘Elizabeth’); William Sampson (and his wife Jane Lang); William Sampson (and wife Frances Gregory); Jane Sampson (and her husband John Dart). William Dart Edith’s father, is John’s son.

Broadwoodkelly and Beyond: South Tawton: North Tawton

For several centuries the Sampson family branch from which Edith’s grandmother Jane came were based in South Tawton, a large parish tucked into the edges of the northern moorland folds.

Old photo of Road approaching South Tawton

You can get a glimpse of the parish during these times from the following passages taken from SOUTH TAWTON PARISH COUNCIL THE FIRST 50 YEARS:

… some were modestly well off, as tenant farmers, small property owners, or as successful tradesmen, blacksmiths, tailors, boot & shoe makers, innkeepers, or, for a few, as skilled manual workers, carpenter, masons, thatchers and so on. But the majority of the population lived at a poverty level, uncertain of work and paid at minimal level when employed (Nine tenths of the women in the parish, (all of the poorest class) are spinners and are regularly supplied by the serge makers with constant employment. Throughout the 19th century the bulk of the population were dependent upon farming for their livelihood, and the majority of men and boys were employed, when work was available, in one or other class of farm work. These labourers lived with their families in small and overcrowded houses in the villages or hamlets of the Parish earning their living from the, often seasonal, work on farms and, at least in the early part of the century, frequently dependent on the charity of the Overseers of the Poor and the Church for the workless periods… The majority of the labourers wives were fully engaged in housekeeping and child bearing and rearing, but, for the first half of the century as Eden describes in the "State of the Poor", there was a sizeable cottage woollen industry in the locality, which employed a few widows, wives, and daughters as spinners and weavers of wool in their cottages. The industrial woollen factory, Pearce's in Sticklepath, employed many more, mainly young unmarried women, from the villages of Ramsley, South Zeal and South Tawton until its closure in the mid 19th century.

A couple of archival documents and censuses suggest possible homes and occupations, allowing us glimpses into fragments of the South Tawton Sampson family’s lives. For example, we can work out a little about the lives of William and Frances Sampson and their children. The family seem to have very evident traces in South Tawton during the late C18 and early C19. It might be this William Sampson who took a Mary Gregory as apprentice in 1785. Was he a yeoman in the parish, as were his distant cousins back in Broadwoodkelly where his ancestors were from? Was Mary a close relation of his wife Frances? Perhaps sister, or niece? Land Apportionments for 1847 for South Tawton show a Robert Sampson occupier of a house and garden in the parish; he could be Robert, William and Frances’ eldest son and eldest brother of Jane, Edith Dart’s grandmother. Similarly, an Oliver Sampson rents house and garden at a hamlet of South Tawton called Ramsley and is also renting other property and or land, a garden at Burgoins and four acres at Town Barton and another plot at Holmeses. Oliver also has part share of a couple of plots with another man called George Westaway. Oliver is probably another, younger son of William and Frances, born in 1796. A Mary Sampson is named on the land census as tenant at the large and probably ancient farm at Cesslands. She may be another daughter of the family, or more likely, a widow of one of the sons. Turning to A2A Discovery: an abstract of a Will in 1807 for Caleb Sampson (Cessland/Sessland), may be that of the same William Sampson’s uncle, who was born in 1736. He must be the same Caleb of Sessland, who takes in Samuel Gillard a ten year old apprentice in 1841; a number of other apprentices are taken by Caleb in the years running from circa 1830-up to 1841. I’m tentatively suggesting that an earlier generation of the family – possibly beginning with the Caleb Sampson who seemingly moved over to the parish from Winkleigh (marrying a mysterious ‘Elizabeth’ whose surname as yet is not known) - took over Sessland after this marriage. Possibly earlier generations of the family were farming there. These references taken together suggest that, as with the Sampson kin over at Broadwoodkelly, many of the South Tawton Sampsons were more than likely farming.

I think though that the branch of the family whose descendants included Jane wife of John Dart, were, by the time of her generation no more established yeoman of their own farms; more likely the decline in agriculture, which happened as the C19 unfolded, had an impact on them and so during Jane’s lifetime the menfolk were probably tenant farmers, or/and agricultural workers.

Like their cousins over in Broadwoodkelly, by the end of the C18 and early C19 the South Tawton branches appear to have an extended intermarried and complicated family in the parish and surrounding villages; many more hours of research hours are needed to be sure about matching names and places. I’ll have to leave this delight to others (and indeed I believe some researchers have already made studies of this cluster of the family), but for the purpose of this piece I shall restrict further commentary to tracing just a little of the family of Edith Dart’s great grandmother Frances (Gregory) Sampson.

Frances; a Devon author’s Great Grandmother

I've not yet had a chance to find out about Frances Gregory's family back in North Tawton where she was baptised. Gregory is a well-known longstanding North Tawton name and the family have for generations intermarried with branches of the Sampson family. I've concentrated on exploring Frances' life as mother following her marriage. In 1851 Frances Sampson, who I believe was mother of Jane Sampson (Edith Dart’s great grandmother and grandmother respectively) aged 86 is living (or staying?) at ‘Woodhouse’ farm with one of her sons and his family. Her husband, William from the Sampson ancestral line, must already have died. Aaron Sampson is I believe Frances’ youngest son from her family of 10-11 siblings; 58 years old, he is named as agricultural labourer. Wife Harriet and 4 children are named along with Frances, now not only a widow, but rather sadly, also labelled as ‘pauper’.

|

| 1851 Census showing Frances Sampson (Pauper) with her family |

Woodhouse is a farm which I think is nowadays designated as in the parish of nearby Spreyton, but it may in the past have straddled several parishes, including nearby Bow.

|

| Scenes around Spreyton Church |

In 1842 Woodhouse was about 120 acres. According to one source online Woodhouse was owned in the mid C19 by the Battishill family. Eventually the farmland was assimilated into the nearby farm of Week and the farmhouse used to house farm labourers, which probably explains why the Sampsons were living there. Apparently Woodhouse is reached by a drive off the Spreyton-Bow road and from a path from nearby Week, but back in the years when this Sampson family were there you could probably reach it from another path between Spreyton and Spreytonwood Water road.

Frances Sampson had probably lived with her youngest son Aaron for many years. She’s listed with his family ten years before, in the 1841 census; the family are at Higher Langabeer farm, a farm bordering Sampford Courtenay some six or seven miles west of Woodhouse.

|

| 1841 Census Frances at Langabeer |

|

| Map showing both Woodhouse and Langabeer Farm |

75 years old, Frances is named with Aaron’s wife, and their son George. There’s also Maria (21), who people on ancestry usually record as Frances’ youngest daughter, but who realistically cannot have been; by 1820, Maria’s baptismal year, Frances would have been well over fifty! I believe Maria must be illegitimate daughter of Frances’s daughter who was also called Fanny. Perhaps her grandmother took the child in and brought her up… (Interestingly a census sample for 1851 records Fanny Sampson (Maria’s mother), as house servant at nearby Oxenham House). By the end of 1851 Frances, William’s widow, has died, presumably while she was with her family at Woodhouse. As mentioned above, she was born and married in nearby North Tawton (1765 and 1785 respectively) so had probably never moved far away from her childhood home. (And here, time allowing I’d love to go on another genealogical recce to explore the Gregory family descent, for our Broadwoodkelly Sampsons also interrelate with the family).

In 1841, Jane, Frances’s eldest daughter was, as I noted earlier in this piece, married and living in Crediton. Jane is about 45. The couple have five children: Samuel (20); James (15); Maria (13); Elizabeth (11) and William (who years later would be father of Edith Dart), their youngest, who is eight. Presumably, Jane, with William and some of his siblings would have travelled across from Crediton to the farmhouse over in the rural backwaters near Sampford Courtenay, to visit her mother and brother and family. Ten years later, in the early 1850s, journeys to visit Frances over at Woodhouse farm would have been shorter. By then William’s grandmother was nearing the end of her life; her youngest son and still living with his parents in 1851, William could easily have accompanied his mother as she spent time with his ailing grandmother back in South Tawton.

Finding the Farmhouses

As noted in Remembering Edith Dart Edith Dart’s immediate paternal family, especially her father William, were established and increasingly respected local builders; but her agricultural farming family legacy linked with her Sampson grandmother may have influenced her as writer when she was growing up, perhaps providing backdrops and backstories for the fictional characters she created. Although Edith’s grandmother on the Sampson side had died in 1865, several years before her youngest granddaughter’s birth in 1872, Edith’s older sisters must have known Jane as at the age of 72, in 1861, their grandmother was still living with her son and his young family in Fountain Court, Crediton. I guess there were cousins from the extended family still living in and around South Tawton who her father and his kin may have kept in touch with. I imagine that Edith Dart picked up the tales told her by her father about his visits to his grandmother’s home in the farmhouse back in South Tawton and he may also have related folk tales about forefathers and foremothers in the rural hideouts of the Devon villages, hamlets and farms lying under moor’s rim.

I know as poet sometimes I return to the tales told me about people in my parents’ families who I never had the chance to meet, including grandparents who’d died before I was born, and their parents. And amongst the vivid memories of special places in childhood we all carry mine include a farm house in the depths of mid Devon, where my own father Laurence Sampson loved to take us as he rekindled his own nostalgia for the place. The farm had a mixed effect on me. Dark and brooding and atmospheric, yet at the same time, its inhabitants, Dad’s first cousins, always gave us a warm welcome, and their Devon teas were to die for. The obligatory huge open fireplace pervaded the place, gave it its sense of unfathomable history; its evocative mystery. We were cocooned within the crocks and fire-irons around which we all sat brooding as our father and his cousins caught up with the latest 1950,’s farm gossip.

Coulson is situated between the villages of Winkleigh and Broadwoodkelly and is still as far I know a working farm. One of the many such inhabited by a long stream of Dad’s farming forefathers - where, back in the 1950’s, his cousins John and Henry and John’s wife Edie still farmed and where (though I wasn’t consciously aware of in those days), a tangled family network had previously unfolded.

The family included Dad’s grandmother, Nancy Earland Sampson Paddon, who I assume moved to Coulson after marrying Bartholomew Paddon following her first husband John Sampson’s death. Meanwhile, Nancy’s daughter Jinny married Bartholomew’s son, another Bartholomew. Both Nancy and Bart. had families who in turn intermarried and had their own children. A complex affair! (And they say modern family set ups are complicated!) Coulson may have been inhabited by one or other of the family networks (Sampsons/Paddons et al) for many generations. Certainly Dad often spoke of his grandmother, Nancy, my great grandmother. Our family is still in possession of a couple of evocative old photos of the farm including at harvest time, with members of the extended family gathered around, eating, chatting, laughing.

When we visited in the 1950s it was as if we’d returned to the world of our departed kin. The long table covered with white damask and spread with Devon cream-laden tea - scones, Victoria sponge, junket, jellies, trifles and steaming tea. All set in front of a long straggling bench, a delight for young kids. Pewter pots and pans hung round the walls. Portraits of Victorian clad ancestors on the whitewashed walls. And in the here and now of then, Dad’s cousins, one swarthy, jocular and friendly, the other a silent broad shouldered man, whose Devonshire accent when he spoke was so broad even we brought up with the dialect could not follow…

But I must not let myself get carried away… I just wanted to explore how even the rustic nostalgia cast by a rural Devon family background can remain in one’s heart and pop up sometimes needing to be resurrected as fiction; or in my case, as poetry…

I must return to Edith’s novel Sareel.

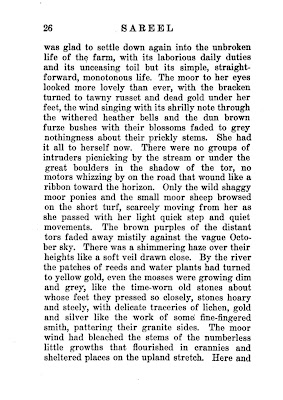

Sareel, the young girl heroine orphan in the novel, herself utterly immersed in the physicality of moor through her new home and work as farm servant, soon finds the local Genius loci has entered her very being. See for example the following page from the novel’s early chapters:

|

| From Sareel |

The woman who created her young heroine knew first hand how Devon’s landscape can hook you and I believe, like her great friend Mary Willcocks, Edith Dart took her father’s forebearers and their countryside homes to heart, transforming her own observations and her father‘s memories and nostalgic recollections into the beating centre of her romantic Devon moorland novel.

Sareel must have made an impression on the literati of her time for the book was apparently made into a film. I just wish I could locate it. Perhaps someone else will?

I can’t judge the literary quality of Edith Dart’s other novels for reasons I’ve already explained. I'd need to have a chance to read them, which I hope will happen one day. But isn’t it odd, isn’t there something amiss, when novels by male authors of her, or of her near contemporary local male writers, such as Eden Phillpotts are remembered, praised for the way they record and bring local characters and places to life and indeed, are still in print? For example see this link to an assessment of a novel based in South Zeal, the joining village to South Tawton (where Edith Dart’s Sampson ancestors were from), by the acclaimed Phillpotts:

Oxenham house was brought to life by EP The Oxenham Arms and Captain John Oxenham have been written about in many, many books and novels over its 850 years of existence . Charles Kingsley's "Westward Ho" describes how Oxenham and the book "The Beacon" by the author Eden Philpotts was entirely written about and around The Oxenham Arms and a fictional barmaid Lizzie Denshaw and the beautiful and strong characters of the village of South Zeal …https://www.theoxenhamarms.com/history

I understand that as I write up this post there’s an amazing and long due project afloat to bring Edith’s friend M P Willcocks to the attention of contemporary readers and interested local communities. My hope is that eventually a similar gathering of community and attention will revivify Edith Dart and her writings from the dark basement of the archives where they currently reside; perhaps this post may encourage someone to bring her work into print again, and so gradually reintroduce her books back into the canon of C20 novels. One day perhaps our missing legacy of as yet abandoned Devon women novelists from the early decades of the C20 will be lifted out of the shadows again ...

Still, if nothing else, it’s been fun to have an excuse to follow the genetic trails of the Devon Sampson clan as it leaves us fast-receding into our home landscape’s past.

(If anyone coming across this is interested in the Sampson family of Broadwoodkelly and its possible links with Jane Sampson's ancestry, I've set out the possible line on Tribal Pages. Just contact me for passwords etc.)

No comments:

Post a Comment

Comments welcome!