Writing Women in the Devon Landscape

Land as Language

Backgrounds

Sigils from the Ridge

|

| Photo Julie Sampson |

I was born at Wildridge, a house built by my paternal grandfather on a ridge overlooking North Tawton, a small town in the centre of Devon. From the ridge just north of the parish as you stare seven crow-miles north into the distance, a panorama draws your gaze right across, then over the town, with Cawsand (or Cosdon), tor and the blue-waves of Dartmoor receding into the far west horizons looking toward Cornwall. North Tawton has a special and rather mysterious history, because of the once important Roman site on its outskirts and its setting within the recently identified and enigmatic 'nemetona' lands (see for example Roger Deakins' Wildwood: A Journey Through Trees).

I've sometimes wondered if country children of the nineteen-fifties post-war generation grew up intuiting that the rural landscapes of their own gardens, farmlands and village territories were surrogate texts, which they learned to read, interpret and make their own. For me, flowers and plants became proxy poems, a lens into a primitive poetic language. Snowdrops in the tiny garden copse by the garden swing were tiny pearl buttons clasping together splits in a childhood mind; daisies were white shreds, their filigree edgings confetti, or shaken snow; buttercups in the hedge, gold in our hearts, were sun-saucers burning my friend’s chin; gooseberries were mini-micro earths in green veined in light.

The link was two-way, from book to place and place to text, a simple, unbreakable, bond. As soon as we (my friends and I) could read, land became a palimpsest, a blank canvas, upon which we could read our texts; even devour them.

Land became text; text merged into land; one fused with the other. Leaves, branches, twigs, flowers, fruits, shrubs, vegetables, all were as script. Woods; trees; hedges; fields; gates; paths; tracks; clouds; stars; all had their own meaning and were inextricably bonded with a chain of texts; the environment came into focus through the filter of a textual screen.

In those 1950’s mid Devon meadows, alive in the thriving grass are all the forever words of texts we read as girls those hot afternoons; often snuggled up in chicken-coops left in the field; sometimes on the top of a hayrick cocooned between sweet-scented hay and the tarpaulin-covering; or even, occasionally, at the very apex of the Douglas-fir at the bottom of the garden, where like monkeys, we threaded through the tracery of green fronded branches, manoeuvring into and onto the wooded-planked camp that my brother and his friend had constructed there. Looking down on the fields below with our books and our comics, we lazed away endless summer days.

Yes, I know the years of the 1950's were decades before the introduction and intrusion of our society's now all consuming world of cyberspace, but back then, as we roamed around the fields near our home, and further afield, my friends and I simultaneously meandered in a reflecting virtual landscape of textual countryside, in which all the children in the books we had ever read lived within their own stories. We were living in them, recreating them, inventing and weaving more stories about them.

As we grew, we devoured all the children’s books in the town-library. They were stored behind a wire grating in the town-hall in North Tawton, which had to be unlocked before we could explore the treasures inside. During this post-war period, the council could not afford to keep up new library stocks, so new books, new worlds, especially new children’s books, arrived rarely. Every time, through the local grape-vine we heard that a batch of new books had arrived, we rushed down town to discover the new arrivals. What children would be living in the new books? What adventures would they get us into? What would their homes, their gardens, their worlds be like? Some of these books, but not all, were by women authors, particularly Americans. It seemed that American rural landscapes were synonymous with English, or British ones. Other than Beatrix Potter, there seemed to be few British women writers of children’s fiction. And, as for a Devon woman who wrote for children, well the possibility didn't enter my mind. So it was the trio Saville, Lewis and Ransome, men rather than women writers, who mirrored our English children’s rural idyll landscape. Malcolm Saville’s Shropshire's 'Long Mynd', playground for the lone-piners, was our Dartmoor, which as the crow flies, was always and everyday there on the horizon some four miles south of our town. The mysterious, heather covered slopes of Shropshire’s Mynd were easily layered on top of our moorland. ‘Witchend’, was 'our' home, ‘Wildridge'; both were merged into the ‘lonely farmhouse’ where the children began their Lone Pine Club. I drew on my inner-map of our home-lands to match the text of Peter’s (Petronella’s) dream of ‘trees in the spinney’.

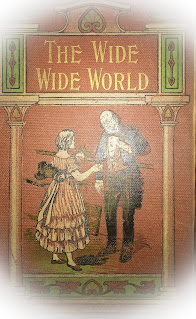

But it was up in the attic at home, where I stumbled upon my first authentic literary buzz, the zest of serendipitously discovered text. There, behind the door, in the bedroom, set snug under the smallest of the two dormer windows in the front of the house looking out over the tor of Cawsand beacon, in the long low cupboard under the eaves, the place where every autumn my parents laid out and stored apples from our orchard - where there were items of quirky family memorabilia, including grandfather’s skating-boots and a gas-mask from the war - was also a small heap of old hardbacks. Dusty. Lightly mildewed. The tangy apple-aroma of the place mingled with woody almond-scented musty browning paper, such as can still create a little frisson in archive basements. One of the books had a brown cover with black and gold stripes and another, a dark green one, was striped black-brown.

All had titles in black writing. One was called The Wide Wide World; the second was Queechy and the other was The Old Helmet. A trio of novels by Susan Warner aka Eizabeth Wetherell.

Hardly the appeal of a contemporary Harry Potter novel, but once The Wide Wide World was retrieved from the dusty stack and I’d read the opening lines, I slipped into the page, into the book and was lost in the world of Ellen Montgomery. I became her sister. Then, became her:

Ellen, in The Wide Wide World, was enchanted as she rambled about in the woods and fields with her beloved friends; so was I, with mine: I was also her; her pleasure in and around the rural town of Ventnor was also mine; it mattered not that Ventnor was in America. After I’d finished Ellen’s story and had recovered from the grief of losing her, I delved into Fleya’s story, in Queechy. I tried The Old Helmet, but that is a more hazy memory, for Helmet did not entice. Ironically though, I've found that that novel actually features at least one reference to ferns growing in ‘profusion in a wild place in Devonshire’, which confirms how insignificant specific localities were at that stage in life.

These books by Elizabeth Wetherell, left in the attic by either my grandmother, mother, or aunts, intermingled with the delights of many others, mostly more up to date adventures and mysteries, bildungsroman, secret-garden and school stories, became stock canon of our nineteen-fifties reading-lists. Anne of Green Gables, Tom’s Midnight Garden, Little Women, Little Men, Anne of Green Gables, The Secret Garden, What Katy Died, Pollyanna, Rebecca of Sunnybrook Farm, Heidi, Malory Towers, Secret Seven, Famous Five, Seven White Gates and all the Lone Pine adventures, Swallows and Amazons, The Coot Club, Wind in the Willows, Lorna Doone, Children of the New Forest, The Lion, the Witch and the Wardrobe, Black Beauty, Children of the New Forest, Jane Eyre, Rebecca of Sunnybrook Farm. The lost goes on ...

Not only did we identify the sites of places in our books, we also began to formulate our own mystery or adventure sites; these became places in our locality which we knew were as special as those we hooked up with the text-places. We took our improvised characters into these places with us and told ourselves stories we had shaped into a weave of fantastic adventures.

But, as I grew up, and, later, began to study literature more seriously, I began to wonder why, except for one or two exceptions (I can hear some of you who might come upon this blog saying 'Enid Blyton' - and yes you are absolutely right, and yes I believe Blyton did set at least one book on Dartmoor and yes, I did read her avidly; she could have a post all to herself here, time allowing) most of those writers who I'd heard of as a child tended to be men, or American. Yes, of course, now I know that there were women authors from my country who wrote novels for children set against Devon backgrounds; Elizabeth Goudge was one of them. Her Little White Horse, set in the Devon landscape, has become a classic of children's literature and published in 1946, was well in time for me and my friends. BUT, it did not appear on our local library shelves in the 1950s and as in the 1950s many families (including ours) did not have too much money to spend in bookshops, sadly, Little White Horse passed me by.

So I did not know about Goudge. Looking back I wonder if the start of my own interest in Devon women who wrote in and about Devon's territories began then. There was a black hole in the books I'd read. I may have wanted to find what was, apparently, missing.

Land became text; text merged into land; one fused with the other. Leaves, branches, twigs, flowers, fruits, shrubs, vegetables, all were as script. Woods; trees; hedges; fields; gates; paths; tracks; clouds; stars; all had their own meaning and were inextricably bonded with a chain of texts; the environment came into focus through the filter of a textual screen.

In those 1950’s mid Devon meadows, alive in the thriving grass are all the forever words of texts we read as girls those hot afternoons; often snuggled up in chicken-coops left in the field; sometimes on the top of a hayrick cocooned between sweet-scented hay and the tarpaulin-covering; or even, occasionally, at the very apex of the Douglas-fir at the bottom of the garden, where like monkeys, we threaded through the tracery of green fronded branches, manoeuvring into and onto the wooded-planked camp that my brother and his friend had constructed there. Looking down on the fields below with our books and our comics, we lazed away endless summer days.

Yes, I know the years of the 1950's were decades before the introduction and intrusion of our society's now all consuming world of cyberspace, but back then, as we roamed around the fields near our home, and further afield, my friends and I simultaneously meandered in a reflecting virtual landscape of textual countryside, in which all the children in the books we had ever read lived within their own stories. We were living in them, recreating them, inventing and weaving more stories about them.

As we grew, we devoured all the children’s books in the town-library. They were stored behind a wire grating in the town-hall in North Tawton, which had to be unlocked before we could explore the treasures inside. During this post-war period, the council could not afford to keep up new library stocks, so new books, new worlds, especially new children’s books, arrived rarely. Every time, through the local grape-vine we heard that a batch of new books had arrived, we rushed down town to discover the new arrivals. What children would be living in the new books? What adventures would they get us into? What would their homes, their gardens, their worlds be like? Some of these books, but not all, were by women authors, particularly Americans. It seemed that American rural landscapes were synonymous with English, or British ones. Other than Beatrix Potter, there seemed to be few British women writers of children’s fiction. And, as for a Devon woman who wrote for children, well the possibility didn't enter my mind. So it was the trio Saville, Lewis and Ransome, men rather than women writers, who mirrored our English children’s rural idyll landscape. Malcolm Saville’s Shropshire's 'Long Mynd', playground for the lone-piners, was our Dartmoor, which as the crow flies, was always and everyday there on the horizon some four miles south of our town. The mysterious, heather covered slopes of Shropshire’s Mynd were easily layered on top of our moorland. ‘Witchend’, was 'our' home, ‘Wildridge'; both were merged into the ‘lonely farmhouse’ where the children began their Lone Pine Club. I drew on my inner-map of our home-lands to match the text of Peter’s (Petronella’s) dream of ‘trees in the spinney’.

But it was up in the attic at home, where I stumbled upon my first authentic literary buzz, the zest of serendipitously discovered text. There, behind the door, in the bedroom, set snug under the smallest of the two dormer windows in the front of the house looking out over the tor of Cawsand beacon, in the long low cupboard under the eaves, the place where every autumn my parents laid out and stored apples from our orchard - where there were items of quirky family memorabilia, including grandfather’s skating-boots and a gas-mask from the war - was also a small heap of old hardbacks. Dusty. Lightly mildewed. The tangy apple-aroma of the place mingled with woody almond-scented musty browning paper, such as can still create a little frisson in archive basements. One of the books had a brown cover with black and gold stripes and another, a dark green one, was striped black-brown.

All had titles in black writing. One was called The Wide Wide World; the second was Queechy and the other was The Old Helmet. A trio of novels by Susan Warner aka Eizabeth Wetherell.

Hardly the appeal of a contemporary Harry Potter novel, but once The Wide Wide World was retrieved from the dusty stack and I’d read the opening lines, I slipped into the page, into the book and was lost in the world of Ellen Montgomery. I became her sister. Then, became her:

Ellen betook herself to the window and sought amusement there. The prospect without gave little promise of it. Rain was falling, and made the street and everything in it look dull and gloomy ... But yet Ellen, having seriously set herself to study everything that passed, presently became engaged in her occupation ; and her thoughts travelling dreamily from one thing to another, she sat for a long time with her little face pressed against the window-frame, perfectly regardless of all but the moving world without. (Wide Wide World)

Ellen, in The Wide Wide World, was enchanted as she rambled about in the woods and fields with her beloved friends; so was I, with mine: I was also her; her pleasure in and around the rural town of Ventnor was also mine; it mattered not that Ventnor was in America. After I’d finished Ellen’s story and had recovered from the grief of losing her, I delved into Fleya’s story, in Queechy. I tried The Old Helmet, but that is a more hazy memory, for Helmet did not entice. Ironically though, I've found that that novel actually features at least one reference to ferns growing in ‘profusion in a wild place in Devonshire’, which confirms how insignificant specific localities were at that stage in life.

These books by Elizabeth Wetherell, left in the attic by either my grandmother, mother, or aunts, intermingled with the delights of many others, mostly more up to date adventures and mysteries, bildungsroman, secret-garden and school stories, became stock canon of our nineteen-fifties reading-lists. Anne of Green Gables, Tom’s Midnight Garden, Little Women, Little Men, Anne of Green Gables, The Secret Garden, What Katy Died, Pollyanna, Rebecca of Sunnybrook Farm, Heidi, Malory Towers, Secret Seven, Famous Five, Seven White Gates and all the Lone Pine adventures, Swallows and Amazons, The Coot Club, Wind in the Willows, Lorna Doone, Children of the New Forest, The Lion, the Witch and the Wardrobe, Black Beauty, Children of the New Forest, Jane Eyre, Rebecca of Sunnybrook Farm. The lost goes on ...

Not only did we identify the sites of places in our books, we also began to formulate our own mystery or adventure sites; these became places in our locality which we knew were as special as those we hooked up with the text-places. We took our improvised characters into these places with us and told ourselves stories we had shaped into a weave of fantastic adventures.

But, as I grew up, and, later, began to study literature more seriously, I began to wonder why, except for one or two exceptions (I can hear some of you who might come upon this blog saying 'Enid Blyton' - and yes you are absolutely right, and yes I believe Blyton did set at least one book on Dartmoor and yes, I did read her avidly; she could have a post all to herself here, time allowing) most of those writers who I'd heard of as a child tended to be men, or American. Yes, of course, now I know that there were women authors from my country who wrote novels for children set against Devon backgrounds; Elizabeth Goudge was one of them. Her Little White Horse, set in the Devon landscape, has become a classic of children's literature and published in 1946, was well in time for me and my friends. BUT, it did not appear on our local library shelves in the 1950s and as in the 1950s many families (including ours) did not have too much money to spend in bookshops, sadly, Little White Horse passed me by.

So I did not know about Goudge. Looking back I wonder if the start of my own interest in Devon women who wrote in and about Devon's territories began then. There was a black hole in the books I'd read. I may have wanted to find what was, apparently, missing.

No comments:

Post a Comment

Comments welcome!