The following blog-page is an extract from a longer reflection about the medieval poet Marie de France and her possible links with Devon:

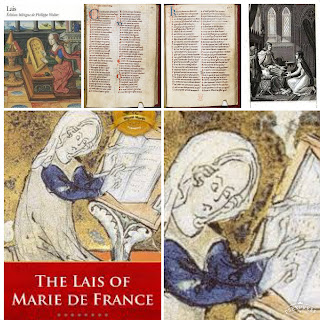

Fragment from translated text of

Marie de Meulan's Eliduc

(see The Lais of Marie de France,

translated by Glyn. S Burgess & Keith Busby)

Sometimes a research path leads to a discovery that stops you in your tracks. Such was the one that took me, unexpectedly, serendipitously, directly to the medieval mystery poet Marie de France. It's a trail of familial complexity pursued in the central heartlands of Devon's high-hedged mazes, the fruits of chance encounters round bends in virtual archives, which may provide new clues about the identification of one of the country's earliest woman poets, who happened to be the most puzzling female writer of the C12. It's a genetically cryptic labyrinth, a kind of Devon equivalent of the literary Da Vinci mystery. One or two researchers have alluded to the poet’s possible connections with Devon, but only in passing. As usual with many literary assessments of our country's history, the possibility of any Devon connection is brushed aside. It is time to reconsider these possible links.

Marie's poems, which experts

consider were composed some time during the latter decades of the C12, are unique.

The poems' lyricism sings out against the violence of the turbulent C12 Baronial

Wars, a period when intense barbarous in-fighting between the main players, Empress Matilda and Stephen et al swept all the way west to Bristol and beyond.[i] Marie the poet's Lays beguile the

reader away from the darkness and draw us into a world of courtly romance,

where, although background battle information (such as that of a castle under

siege), is implicit, the story's main narrative treats us with a fast moving tale of a

knight's seduction within the boudoir of a beauteous princess, who, invariably, is reclining luxuriantly on her silk-lined bed.

Marie de France's poems' display a keen familiarity with the topography of the South West, they include several that are littered with names of Cornish places. This has led to several researchers concluding in passing that the poet may have lived at least part of her life amid the Celtic epicentres of the Arthurian legend:

... the lay of Lanval,

Guigemar, Yonec (maybe), and especially those of Chèvrefeuil Eliduc and Milun

whose topography belongs to Devon and south Wales, suggest that their author

lived in this region rich in a tradition celtique.[ii]

And no, you might not associate the

tale of a princess buried away in a castle in Devon with the landscape of

Anglo-Norman mid Devon, which except for interspersed pockets of cultivated

land, must in the C12 predominantly have been 'all

forest and full of woodes brakes and thickets'.[iii]

Exeter castle from Rougemont Gardens

But, Eliduc, the longest of the poet's famous Lays (a C12 generic equivalent of such modern potboilers as Fifty Shades of Grey), tells the story of a happy married man who falls in love with a Devon princess, then leaves his home back in France for a series of escapades, which unfold close to the Devon coast. We are informed that the knight lands at Totnes, is seduced by and then elopes with Guilliadun, a princess, daughter of a king who we are told lived 'near Exeter' in Devon. As the story unravels the local topicality of Eliduc continues, for this poem unravels half of its narrative line within Devon, suggesting that the poet herself was familiar with geography of the area.[iv]

Reading Eliduc, it is tempting to match the medieval Devon princess with one of Devon's then real-life noble-women, who, it could be conjectured, may have been model for Marie's imaginary heroine. And, given that the heroines in Marie de France's lyrics, such as Eliduc's unidentified princess, are usually noblewomen from the highest elite, it is appropriate to wonder if the poet herself also came from that background.

The academic consensus is that the elusive poet probably originated from within an

Anglo-Norman family, who in the expectation of attaining land, or perhaps after

losing their own in France, crossed to England with the Conqueror. It’s

possible that because of her family situation Marie might even have needed to

protect her writerly identity through an assumed name. Likely to have been born

in France, she presumably then spent at least some of her life in England where,

embedded in the heart of the high elite, her family were famed for their

interest in learning and literature. Some researchers believe that Marie may

have had close links with the royal court, either as niece of William theConqueror, or as an illegitimate daughter of one of his family:

Some of the most widely

accepted candidates for the poet are Marie, Abbess of Shaftesbury and

half-sister to Henry II, King of England; Marie, Abbess

of Reading; Marie de Boulogne; Marie, Abbess

of Barking; and Marie de Meulan, wife of Hugh Talbot.[v]

Recently, most of the above women

have been excluded from the list of possible candidates for the poet, except

that is for the last named, Marie, daughter of Waleran de Meulan Beaumont and

his wife Agnes Montfort. It is Marie’s husband whose possible Devon provenance

has led researchers to suggest a tenuous link between the poet and the

Southwest. He was Hugh Talbot, Lord of Hotot-sur-Mer, of Cleuville (a place

identified by some as Clovelly), whose extensive lands apparently included

holdings in Devon....

[i] For example, re the warring background in South West

England we are told that

The castle at Bristol had been strongly

fortified by Earl Robert and stored with plenty of provisions. It later became

the main headquarters for Matilda's supporters. From Bristol, the barons would

make frequent inroads to the inhabitants in the towns and with barbarous

violence and torture, took all their money and properties. (From the Past We Came -

http://sexygeekygirl1.blogspot.co.uk/2012/08/stephen-and-matilda-cruel-civil-war_20.html).

[ii] See in The

Cygne, Journal of the International Marie de France Society, vol 4, 2006.

[iii] Hooker see in Transactions

of the Devonshire Association, vol. 47, 1917.

[iv] Read Eliduc

in Mary Lou Martin, The Fables of Marie

de France; an English Translation (Summa Publication 1984).

[v] See 'Marie de France', New World Encyclopedia online.

No comments:

Post a Comment

Comments welcome!