I ... Ilfracombe

|

| Scenes around Ilfracombe Photo Julie Sampson |

A - Z of Devon Places and Women Writers

|

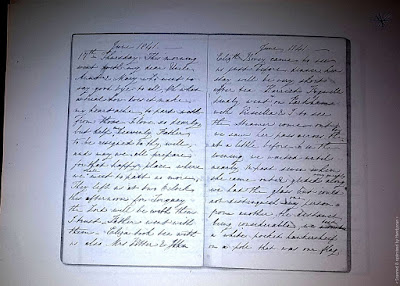

| Said to be Rev., John Chanter and his wife Charlotte Kingsley Chanter outside their vicarage home in Ilfracombe. (Photo copy from Ilfracombe Museum) |

Ilfracombe has enticed various women writers and in this A-Z it was the obvious choice to represent 'I'. Most famously, although she was a visitor to Devon, George Eliot stayed in the town in 1856, at the beginning of her literary career. Her contemporary, Charlotte Chanter, daughter of Reverend Charles Kingsley, and sister of the more famous authors Charles, Henry and George was local and is the central focus of this blog piece. Charlotte wrote several novels, including Over the Cliffs as well as a travel memoir, Ferney Combes, 1856, an unusual book about her driving tour with husband across Devon looking for ferns.

Charlotte Chanter (1828-1882) in 1856 wrote a short ‘guide’ book to the area around Ilfracombe and dedicated it to her parents, the Rev. Charles and Mrs Kingsley. Charlotte illustrated her book with her own drawings of ferns and (her own) map of Devonshire. The map details the areas of her own excursions, largely along the north coast and Dartmoor. Although the first edition did not include the map, one was included in the second and third editions. (See Victorian Maps)

As writer, Charlotte Chanter's susceptibility to the charms of her home county is often evident in her fiction, as Simon Trezise notes in his book, (See passages below):

|

| Taken from Simon Trezise's The West Country as a Literary Invention |

|

| Taken from Simon Trezise's The West Country as a Literary Invention |

Although she was born in Lincolnshire, in 1828, Charlotte probably spent most of her childhood in Devon sharing childhood escapades in Clovelly, where their father was rector, with her more famous author brothers Charles, George and Henry. Her eldest brother Charles was born about ten years before his youngest sister, at Holne on Dartmoor, during a period when their father was curate in charge of the parish and after a spell away from Devon the family returned to Clovelly when Charlotte was three years old and stayed there for five years. Charlotte was seven when her father temporarily moved to Ilfracombe before taking up a new incumbency in Chelsea. I do not know when or how Charlotte met John Mills Chanter, but presumably they knew each other from the time of her childhood as I've read that Chanter met up with the Kingsleys in Clovelly in the early 1830s, Maybe Charlotte knew her future husband from a very early age. It is also said that Chanter was asked to go to Chelsea with the Revd/ Kingsley in 1836, but preferred to stay in Ilfracombe. The couple's marriage took place on May 10th, 1849, at Clifton Church in Gloucestershire when she was twenty and he 41. The Chanters had six daughters and one son. Charlotte died in 1882 at the age of 53 and is buried in the graveyard at Ilfracombe's Holy Trinity Church.

I have included references to George Eliot's Devon story in the book I am writing about Devon's women writers and I've introduced Charlotte Chanter, who was surrounded by men-who-wrote. But this blog-piece focusing on Ilfracombe provides a chance to explore this important Devon writer a little more.

Perhaps, given that two of her brothers, her husband, and at least one of his cousins, all made lasting impressions as authors, vicar's wife and daughter Charlotte Kingsley-Chanter becoming 'writer' herself was inevitable. In some ways, with her intense literary inclined family network, she had no choice.

Much of the material that tells us about Charlotte's life is derived from information about her famous male relations, especially apropos Charles, who features in a plethora of feature articles off and online and whose life is memorialised in local museums, such as The Kingsley Museum, in Clovelly. For the most part his talented younger sister is omitted from these features.

Much of the material that tells us about Charlotte's life is derived from information about her famous male relations, especially apropos Charles, who features in a plethora of feature articles off and online and whose life is memorialised in local museums, such as The Kingsley Museum, in Clovelly. For the most part his talented younger sister is omitted from these features.

|

| Fragment of Family Tree of Chanter family in Devon |

As well as her own, not insignificant writing output, what makes Charlotte Kingsley Chanter especially interesting is that, in parallel with the local male writing network, the writer was also a central figure in a circle of female writers. As yet I have not had much opportunity to explore the network; that is a goal for future research. But even at this early stage I have a hunch that there is a complicated web of a lost literary labyrinth swirling out round the extended networks of family and friends centred on the Chanters and Kingsleys and the north Devon district out and about Ilfracombe. Anyone researching Charlotte should reach out and extend their remit to those around her who also wrote, famous or not. Most intriguingly, although as yet I have not found anyone who has commented on the connections, I believe there must have been some link between the (eventually) more famous George Eliot and Charlotte Chanter. One fragment in a book about Ilfracombe notes that when Eliot arrived in the town, in 1856, she and her partner George Henry Lewes were delighted with 'Runnymede Villa', the lodging house they found through the recommendation of Fanny Kingsley, who was Charles Kingsley's wife and Charlotte's sister in law. In other words, there were already established family associations between Charlotte's family and Eliot and Lewes. I believe others are beginning to trace this important C19 literary network - see for example Vivarium - and look forward to seeing more exploration of it in the future.

But further examination of the links between Charlotte Chanter and Eliot goes beyond the scope of this piece. Maybe one day someone reading this will have information to help fill in the missing jigsaw. Until then, I'm going to make a start into exploring the lost women's literary circle with the Charlotte and Kingsley family interconnections. I note that the female author circle surrounding Charlotte Chanter included (probably) her mother, at least one of her daughters, two of her nieces and a sister in law. Then, delving back in time one generation, it may take in her husband's aunt.

Let's begin with the latter, John Mills Chanter's aunt. I believe she was the somewhat elusive writer called Elizabeth Thomas (see also Elizabeth Thomas), who I've written a little about in my other blog (see Devon Celebration). Elizabeth Thomas appears to have been a sister of John Mills Chanter's mother, Mary Wolferstan Chanter.

It is through Charlotte Chanter's sister in law (wife of her brother Charles), Frances (Fanny) Kingsley, who evidently knew George Eliot (who wrote a biography of her famous novelist husband Charles), that we learn about the Kingsley siblings' mother Mary Lucas Kingsley, who was, says Frances 'a remarkable women full of poetry and enthusiasm'. (See photo below). Google books gives details of a Commonplace Book by her. Perhaps Mary Kingsley's daughter's own literary talents were inherited from her maternal as much as paternal side.

|

| From Frances Kingsley's biography of her husband, Charles Kingsley; Early Days at Holne |

Frances Kingsley (see a photo of her with her husband Charles Kingsley here and more information at Find a Grave) was mother of Charlotte's niece, the novelist Mary St Leger Harrison, (pseudonym Lucas Malet (1852-1931), who was born at Eversley in Hampshire but moved to Clovelly 1876 after marriage to yet another of the clergymen who proliferate in this family, Revd. William Harrison. The marriage did not last; it is said that the couple had financial difficulties and that Mary was ill-treated by her husband, a situation which apparently triggered her to begin writing fiction, the dark tone of which, in turn attracted readers and soon made her a very popular author. In the 1890s the couple separated and Lucas Malet moved away from Devon, although it is said she returned to Clovelly frequently until the death of her husband, in 1897. Novels written by Lucas Malet include The Wages of Sin (1890), The Carissima (1896) and The History of Sir Richard Calmady (1901),

Although, now second decade of the C21, according to at least one biographer, Lucas Malet's reputation as writer has not lasted and she remains a largely ignored author, this underrated novelist attracts more public interest than do the other women writing in her familial and friendly circle. You will find all kinds of online links which explore avenues of interest concerning her life and writings. I would love to have introduced Malet in my own writing about Devon women writers, but unfortunately due to space there has not yet been a chance to do so. At the time she first penned her fiction, Lucas Malet/Mary St Leger Harrison, 'was widely regarded as one of the premier writers of fiction in the English-speaking world'. (See Talia Schaffer's review of Patricia Lorimer Lundberg's "An Inward Necessity"; The Writers' Life of Lucas Malet, in English Literature in Translation vol 47/3/2004) was apparently compared favourably with Henry James, Thomas Hardy and George Eliot. However, following the same cyclic pattern as so often happens with women writers, by the time of her death Lucas Malet, once one of the most successful novelists of her day, was all but forgotten by her previously adoring fans.

Incidentally, Mary St Leger Harrison's own literary acquaintances included another once well-know Devon novelist, Mary Patricia Willcocks, (there is at least one letter sent by Malet to Willcocks held in the Devon Record Office) thus extending the C19/early C20 women writer network outward from the Chanters and Kingsley in north Devon.

Returning to the immediate Kingsley and Chanter families, I must include Charlotte Chanter's other niece and Lucas Malet's first cousin, the explorer/writer Mary Henrietta Kingsley (1862-1900), daughter of Charlotte's brother George, who of all the women so far mentioned here, is the woman/author/explorer who has maintained long-term acclaim. Although she was one of the family, as far as I am aware Mary Kingsley did not have many, if any, direct links with Devon, other than the complex web of immediate kin who had had or still had roots there. She was apparently close to her novelist cousin of the same name (Lucas Malet). One biographer relates an incident when William Harrison, Lucas Malet's husband was ill when Lucas called on her cousin to come and help her; the cameo provides fascinating insight into the inner psychological dynamics of the family.

Last, but not least of this complicated women writer network which extends outwards from Charlotte Chanter, is her daughter Gratiana, who followed the writing career of her mother. Gratiana wrote both fiction and a travel/memoir Wanderings in North Devon Being Records and Reminiscences in the Life of John Mill Chanter, M.A., which appears to be a collaborative memoir written with her father (see also Wanderings) about her parents' life. It is a useful book for providing information about the Chanters' daily life in and around Ilfracombe. We hear about Gratiana's mother Charlotte's love of German; how she translated for magazines. We learn: that of the Chanters seven children, their eldest only son Kingsley died in 1875 in America, at the age of 24; that the family's home in Ilfracombe was at the Old Vicarage, in Braunton Road; that Charlotte placed a bunch of lilies of the valley at the corner stone when the new church was opened in 1851. that the Chanter's had purchased Millslade Inn in Brendon, in 1869. There had been previous travelling holidays, including one to Nice and another to Wales, when Revd. Chanter had been taken ill. We find that Charlotte was friend of the infamous Reverend Hawker of Morwenstow - whose scenery Chanter used in her novel Over the Cliffs and that the Chanter's purchased of Millslade Inn in Brendon, in 1869. Gratiana embellished her edition of her father's memoir with descriptions about special days shared by the family, including how the family spent Christmas.

Gratiana was later the author of The Witch of Withy Ford about which a review commented 'Although there is nothing novel in the plot of Gratiana Chanter's romance, it is vigorously written in old-fashioned rural English' (see The Book News Monthly). She also wroteLast, but not least of this complicated women writer network which extends outwards from Charlotte Chanter, is her daughter Gratiana, who followed the writing career of her mother. Gratiana wrote both fiction and a travel/memoir Wanderings in North Devon Being Records and Reminiscences in the Life of John Mill Chanter, M.A., which appears to be a collaborative memoir written with her father (see also Wanderings) about her parents' life. It is a useful book for providing information about the Chanters' daily life in and around Ilfracombe. We hear about Gratiana's mother Charlotte's love of German; how she translated for magazines. We learn: that of the Chanters seven children, their eldest only son Kingsley died in 1875 in America, at the age of 24; that the family's home in Ilfracombe was at the Old Vicarage, in Braunton Road; that Charlotte placed a bunch of lilies of the valley at the corner stone when the new church was opened in 1851. that the Chanter's had purchased Millslade Inn in Brendon, in 1869. There had been previous travelling holidays, including one to Nice and another to Wales, when Revd. Chanter had been taken ill. We find that Charlotte was friend of the infamous Reverend Hawker of Morwenstow - whose scenery Chanter used in her novel Over the Cliffs and that the Chanter's purchased of Millslade Inn in Brendon, in 1869. Gratiana embellished her edition of her father's memoir with descriptions about special days shared by the family, including how the family spent Christmas.

short stories published in The Rainbow Garden, of which one reviewer noted 'The tales have all the charm of fairy tales, and there is a thread of exquisite fancy running through them' (see Westminster Review).

|

| Extract from The Witch of Withyford Gratiana Chanter |