This year I plan to publish a book about Devon women writers. It is a project many years in the making, and after a prolonged period of revision and reflection, it is now (nearly) ready to move into the world. I'll be posting more about the book in the coming months but as a starter, am here to revive this neglected and flagging blog, which had to be abandoned due to personal circumstances.

So , where better to begin than literary celebrations. Anniversary events. Devon ones I mean.

It has recently dawned on me that 2026 is an appropriate year to pause and take stock of women writers with Devon links. Many people, especially her loyal fans, will recognise it as the fiftieth anniversary of the death of Agatha Christie, Devon’s most celebrated literary figure. But once you begin to look beyond that single, famous name, a richer and more varied story starts to emerge.

In 2026, an intriguing sequence of literary anniversaries brings into focus the long, varied history of women writers connected with Devon. What you might call a long view Devon literary chronology. Spanning a century and a half, these moments offer a way of reading women’s writing through time, place, and landscape.

____________

150 years - 1876

Author FloraThompson was born 150 years ago, in 1876. Though best known for Lark Rise to Candleford, Thompson’s work belongs to a wider tradition of women preserving rural life through memory and observation — a tradition deeply resonant with Devon landscapes. Thompson lived in south Devon for many years.

145 years 1881 - Mother Molly

A novel, Frances Mary Peard’s Mother Molly, one of that writer’s many publications, adds another strand of rural and domestic life to the chronology of celebratory output.

125 years - 1901

In 1901, the mysterious novelist writing as Zack published a novel called The White Cottage. 125 years later, Zack’s work remains little known, yet the work sits at a crucial moment in women’s rural fiction at the turn of the twentieth century. The same year saw the death of one of the then most prolific Victorian authors, Charlotte Yonge, who spent many happy childhood holidays with her cousins at Puslinch.

__________________

100 years - 1926

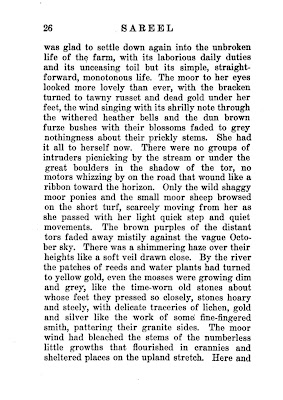

2026 is apposite for its centennial celebrations of Devon-linked fiction and non-fiction. The year 1926, 100 years ago, was especially productive for Devon literary fictional publications by women and also marked publication of several non-fiction books by established women writers. During that year the following novels were published: Sylvia Townsend Warner’s Lolly Willowes, a novel of female independence and chosen solitude; two novels by Margaret Pedler, Tomorrow’s Tangle and Yesterday’s Harvest, both written at the height of the novelist’s popularity; M. P. Willcocks’ Ropes of Sand, one of her later novels, the ‘love story of a middle-aged spinster’; and E M Delafield’s novel Jill, a post-WWI London social novel built around a young woman (Jill) who had an unconventional upbringing; As well as this series of novels two of the period’s most distinctive Devon women writers brought out topographical non-fiction texts which stamped another layer onto Devon’s C20 literary mappings, eccentric author Beatrice Chase’s Dartmoor The Passing of the Rainbow Maker evoking the moor’s people and rhythms; and local historian Beatrix Cresswell’s Sidmouth and the neighbourhood from the Otter to the Axe, a book which speaks to a concurrent fascination with Devon’s local geography and identity.

80 years - 1946

2026 marks 80 years since the death of important author May Sinclair, poet, novelist, and early modernist thinker who lived for several years in Devon. Sinclair wrote fiction and poetry shaped by walking, inward attention, and spiritual enquiry. Her work forms an important bridge between late Victorian writing and twentieth-century psychological exploration.

70 years - 1956

In 1956, 70 years back, popular novelist Elizabeth Goudge, then living in Devon, published her novel The Rosemary Tree. Written during the author’s years in Marldon, the novel draws on a fictionalised South-West landscape shaped by stillness, memory, and inward change.

___________

60 years - 1966

In 1966, 60 years ago, two major twentieth-century novels appeared in forms that reshaped women’s literary voice: Jean Rhys’s Wide Sargasso Sea and Sylvia Plath’s The Bell Jar (its first edition published under Plath’s own name). Both were written out of marginal positions, and both remain central to how women’s interior lives are read today.

__________

55 years - 1971

...'stiff fields of corn grow/To the hilltop' ... 'little white boats/Sag sideways twice every day/As the sea pulls away their prop' (from 'The Estuary', Patricia Beer)

Exmouth born poet Patricia Beer’s poetry collection The Estuary, often considered a key mid career work, was published in 1971. The book’s title poem references the coastal scapes of Beer's homelands."’

2out a

_____________

The Estuary (1971), opens with a wonderful poem which turns the Exe estuary into two contrasted territories representing her childhood home and her future life: on one bank, "stiff fields of corn grow / To the hilltop"; on the other, "little white boats / Sag sideways twice every day / As the sea pulls away their prop".

The Estuary thus establishes and maps poetically for posterity a distinctive Devon landscape, the transitional zone where river freshwater meets and merges with salty seawater. The collection appeared during a time of poetry revival in Devon, when small presses were springing up in various locations, whilst The Arvon Foundation, recently founded, in 1968, was beginning to make its presence known amongst the literary and poetry community both locally and nationally. The following year, 1972, the Arvon Foundation's first and residential location at Totleigh Barton near Sheepwash began to host its range of writer classes, which to this day remains central to writers in all genres and has become famed for its mentoring of so many authors.

Five years before Beer's collection turned one of Devon's classifying landscapes into visionary poetic metaphor, in 1966 a pair of novels arguably written by the two most outstanding female literary figures of the mid C20 were published (The Bell Jar had been published previously but not in Plath's own name) making 1966 an important year for fiction locally and nationally. The Bell Jar and Wide Sargasso Sea have become classics in their genres. Neither novel is usually linked with Devon, and yet Plath’s and Rhys’ lives in their respective homes in Devon powerfully influenced both texts. In the early 1960s, Sylvia Plath was living at Court Green in North Tawton, first with Ted Hughes and later alone. The Bell Jar is set in Plath’s home country, Devon does not feature in any shape or form, but it was in Devon that Plath revised and prepared the book for publication. First issued in 1963 under a pseudonym, the republishing of The Bell Jar's under her own name in 1966, occurred three years after her death. The book’s republication was part of the ongoing posthumous management of Plath’s work. Similarly, Wide Sargasso Sea looks outward to its author's Caribbean past, but it was written and released from a position of physical and cultural marginality in Devon. In 1966, Jean Rhys then in her seventies was living quietly (more or less as recluse) in mid-Devon, in the village of Cheriton Fitzpaine, (a parish less than 20 miles from North Tawton, where Plath had spent her final years). Rhys' letters from this period refers repeatedly to “the novel I am trying to write” — her reimagining of the “mad woman in Jane Eyre” — and to her anxiety that even its title, Wide Sargasso Sea, would not be understood. In one letter she writes

I've dreamt several time that I was going to have a baby/finally I dreamt that I was looking at the baby in the cradle/such a puny weak thing So the book must be finished,/and that must be what I think about it really.

When the novel appeared in 1966, it transformed the author’s reputation after decades of near silence and won both the Royal Society of Literature Prize and the prestigious WHSmith Literary Award.

The Rosemary Tree is 70

Alongside Gentian Hill biographers and critics often feature The Rosemary Tree as one of Elizabeth Goudge's “Devon novels”. Published just a decade before the intensely fractured, rebellious novels of Rhys and Plath, The Rosemary Tree was written during Goudge’s wartime and post-war residence in Marldon, Devon, a time that produced several of her most enduring novels, and left a clear imprint on their settings and themes. Albeit fictional in mode, The Rosemary Tree is rooted in the south Devon landscape.

One commentary on The Rosemary Tree on The Elizabeth Goudge website notes ‘We were all still caught up in the undertow of the war, its pale colours leak through into this sad, earnest book'. Unlike The Bell Jar and Wide Sargasso Sea, The Rosemary Tree represents a true westcountry inheritance of place, continuity, whilst its story and themes are influenced by Goudge's own experiences in Devon:

Later on in the book she uses an experience of her own life in Devon which was one of her own spiritual highlights, a symbol of great hope and beauty. She had gone out into her garden after a fall of snow and had been marvelling at the purity and silence of it all when she heard ” a solo voice, ringing out joy and praise. One would have said it was a woman’s voice, only could any woman sing like that, with such simplicity and beauty? It lasted for some minutes and then ceased, and the deep silence came back once more.” (Goudge 1974 p 138)

The Rosemary Tree has grown in popularity over the years. When I had a quick look at its Amazon rankings recently I noted it is still in the top 800 of books named under 'Cultural Heritage Fiction', which is quite impressive given the novel's age. But I read somewhere that when the book first came out the publishers were unhappy with it believing the its dominant Christian morality would not appeal to a mass market

80 years mark May Sinclair's Death

Whilst Goudge was one of the last novelists whose fiction is steeped in the conventions of pre Modernist writing, the work of May Sinclair (as poet, novelist, critic and philosopher) who died ten years before publication of The Rosemary Tree, was exploratory, at once looking both backwards to the conventions of Victorian fiction and forward to the disruptions of Modernism. Sinclair was and remains an important author, and it's not too much of an extravagation to claim that her time in Devon - where walking, soliture and landscape took a vital part in her creative practice - played a formative influence on her literary achievements and skills.

1926, a Year of Female Devon Fiction

1926 was a prolific year for Devon fiction by women writers. Sylvia Townsend Warner’s Lolly Willowes, Margaret Pedler, Tomorrow’s Tangle and Yesterday’s Harvest, M. P. Willcocks' Ropes of Sand, and E M Delafield’s Jill, novels published one hundred years ago were all authored by women with powerful Devon connections. During this decade significant changes were taking place in Devon’s literary climate, fiction by women was beginning to make a mark on what had been a male dominated book scene. Fiction by a distinguished clique of male writers - including Henry Williamson, John Galsworthy and Eden Phillpotts - made these writers famous and stamped the names of their novels into the history canon. Nowadays its far more likely to be their names and books that remain in the reading public consciousness, although things are beginning to change.

Certainly the fiction outpouring of 1926 is a great opportunity to reinstate the women's names and books and emphasise their Devon connection. Delafield, Pedler, and Willcocks reflect writing lives intrinsically linked to Devon through long residence, local affiliation, and sustained working lives in the county. And although it would be wrong to claim any special link between the book and county, as Sylvia Townsend Warner’s Lolly Willowes predates her later move to the southwest, the novel’s vision of rural retreat and female self determination finds echoes with Warner’s later life outside London.

Pedler is firmly established within the Devon interwar literary culture, even when her fiction itself ranges beyond it. Read now, her novels invite reconsideration not only of Pedler’s popularity, but of the seriousness with which women’s “middlebrow” fiction engaged the social aftermath of the First World War. Delafield’s Jill, published in 1926, precedes Delafield’s later fame as the creator of The Provincial Lady but as with her other earlier fiction is replete with her take on social instability and female improvisation in the post-war years. By the mid-1920s, M. P. Willcocks was an established Devon novelist, and marked by psychological seriousness and moral tension, Ropes of Sand belongs to her later phase of writing.

125 years ago - A Novel and a Death

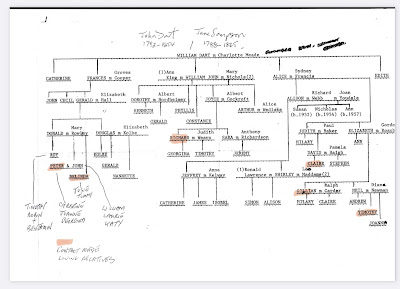

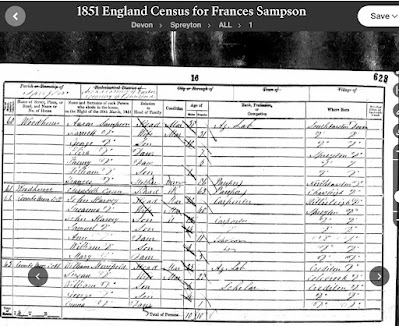

One of the group of Devon women novelists now more of less forgotten preceding by a quarter of a century the flow of new fiction of 1926, was the mysterious writer who used the pseudonym Zack, whose novel The White Cottage appeared in 1901. Zack, real name Gwendoline Keats (1865–1910), was the same generation as, and probably close friend of MP Willcocks and another local novelist /poet called Edith Dart These are important authors in their own right and perhaps one day Zack’s work will be acclaimed and the writer be recognised for her contribution to the literary output of her time. The White Cottage is a novel that looks forward to the huge changes that will come to the lives of women and their fictional representation during the C20. Charlotte Mary Yonge on the other hand, who died in 1901, closes a long Victorian literary life closely associated with Devon. Her death marks a moment of transit as the moral and communal certainties of nineteenth-century fiction began to dissolve into a new period of change and challenge.

1881 - 145 years ago - another Devon novel

1876, a Literary Birth, 150 years past

Please note the anniversary events listed in this post are likely to be representative of other literary commemorations that took place in the years concerned.