Remembering Edith Dart, Crediton’s Edwardian Novelist and Poet; As a novelist in “Miriam,” in “Likeness,” in “Rebecca Drew,” and especially in “Sareel,” Devon lives again'

(Quotation from Obituary for Edith Dart by Mary Patricia Willcocks)

The Grand Affair

|

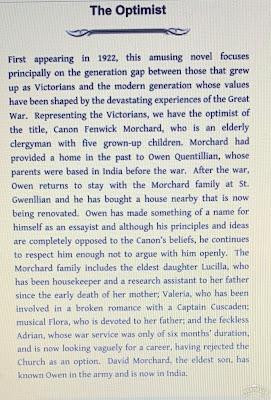

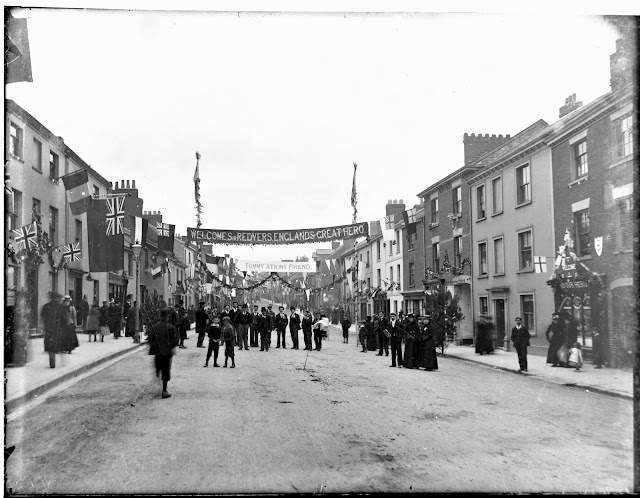

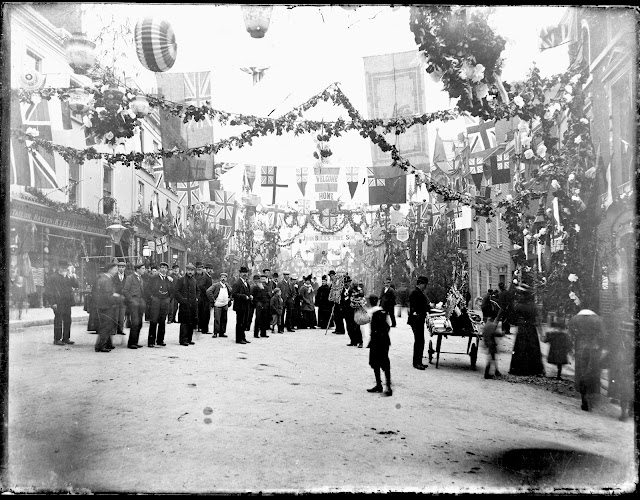

| General Buller's Return to Crediton 1900 I am grateful to staff at Crediton Museum for locating the image. |

‘Miss Edith Dart, attired in a costume of purple tweed with longer black picture hat presented Lady Audrey Buller with a magnificent shower bouquet with red, white and blue favours’. (The Scotsman 2 November 1900).

|

| General Buller's Return to Crediton 1900 I am grateful to staff at Crediton Museum for locating this image. |

As far as I’m aware the vivid depiction in the passage above picturing the young writer and Crediton born woman who, at the time the article from which this quote was written and published in The Scotsman, 2nd November 1900, was about 27, is the only extant description of her. (And it is possible that Edith is in the photo). The passage conjures a vibrant picture, such as, for me, suggests a woman who intends to stand out from the crowd, not someone who prefers seclusion and isolation. For, the occasion about which this feature was written, was by all accounts a grand affair: the return of Crediton’s most renowned hero General Sir Redvers Buller to his home town following a long-standing military career. Buller’s carriage had just come to a standstill outside the railed-off enclosure at Crediton’s then Town Hall steps, bands were striking out 'The Boys of the Old Brigade', and hundreds of local citizens, a thousand children and a detachment of Yeomanry, must have made an arresting greeting-party.

‘The Dart family is deeply rooted in the soil of Crediton, where her father founded the well-known firm of woodworkers and carvers.’ (From M.P. Willcocks, Appreciation/Obituary for Edith)

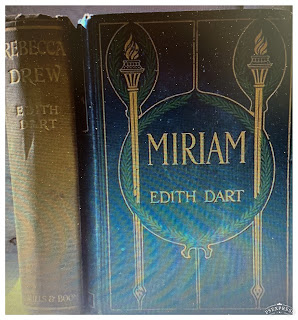

Edith was already an author who had short stories and poems published in a variety of contemporary magazines and anthologies. A years later considerable success was to come her way with publication of a poetry collection, Earth with her Bars and Other Poems and several then acclaimed novels, including Miriam, Likeness,and Rebecca Drew, The Loom of Life and Sareel - which was made into a film. You can find and read Sareel and Earth with her Bars on Play Books App. The other books I'm afraid are very hard to come by. There are copies of them at Devon Record Office, but if like me it's not easy to get there, it's a matter of luck finding a old book still in print (and invariably at a great cost) via the internet.

I'll post about Edith's writing in a second post. Here I'm going to concentrate on her life.

Until I came across the account of Buller’s return to Crediton I’d assumed that Edith, who now. in the C21, is just another of the female authors of her time who many years ago disappeared under the cultural radar, had a fragile disposition and perhaps reclusive personality; someone who retired to her attic to pen her books away from the crowd. And for a while when I sent out tentative feelers this assumption was credible because one of the few facts you can glean about Edith - repeated in the few available sources (apparently originally provided by a niece) - is that she was, or at some point became, an invalid, who for many years was virtually bedridden in her own room.

I think now that Edith's life story was more subtle and complicated than this…

My interest in Edith is twofold. She's an intriguing novelist/poet whose stories and poems predominantly featured Devon landscapes and people - yet another to add to the list of long forgotten female writers. But also as a keen family historian, when I found that her paternal grandmother’s name twinned that of my own – (though Edith's 'Jane Sampson' was a maiden name and mine my paternal grandmother’s married name), I felt immediately drawn to find more about her; perhaps we met somewhere along her grandmother’s/my grandfather’s family lineages.

Also, whilst browsing various archives and internet sources in search of background information about Edith I’d been staggered to discover that, with a couple of exceptions, including her near neighbour Margaret Pedler, rather than being the only mid-Devon woman who wrote during these early decades of the C20, as initially I believed, Edith Dart was one among a crowd of women from Devon who wrote poetry or and fiction during this era. Many of the women I believe were probably linked with one another through a friendship network. Names of others, some of whom I mentioned in my previous post will I hope one day feature on this blog. I don’t know if Edith knew Margaret Pedler, but she was definitely a close friend of Devon’s ‘forgotten feminist’ writer Mary Patricia Willcocks, who wrote the obituary (quoted from above) for her younger friend following Edith’s death in 1922. I found out about MP Willcocks some years ago. Until some of the other contemporary Devon who wrote begin to receive much more long neglected attention M.P.W., Margaret Pedler and Edith Dart almost stand as sole representatives of a cluster of writers who for the most part have disappeared under the radar, although some of their names are beginning to resurface.

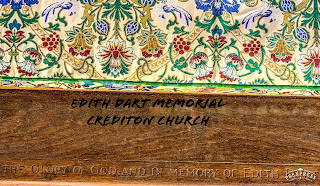

Finding her

… So who was the once acclaimed Crediton writer Edith Charlotte Maria Dart, whose family were evidently closely linked socially with the town’s then foremost family, the Bullers? Presumably it was the achievements of her father, respected builder whose many projects in and around Crediton brought local attention to the family; especially his notable contributions to Crediton’s church. In 1865, seven years before his youngest daughter was born, William Dart had been appointed carpenter to Crediton church corporation and as such was responsible for much of the church furnishings during that time. (Following William’s death the business was taken over by his son in law Sidney Francis (husband of Edith's sister Alice) and family and major church improvements continued, including the Buller memorial and a WW1 memorial plaque in the nave). According to a descendant of the Dart family the firm later became called The Ecclesiastical Art Works.

Edith’s paternal ancestral family had deep roots in mid Devon. William’s father John, born in 1792, had married Jane Sampson (born 1788), who was from another intricate family maze, linked with nearby parishes such as South and North Tawton. (I am attempting to follow the Dart Sampson line to see if/when and where they might have connected with our Sampson family).

Charlotte, Edith’s mother’s family on the other hand were apparently from Kent. I’ve not yet had too much chance to find out very much about their background, but I wonder if Edith's literary interests in part derived from her mother's side of the family. A pamphlet about the Dart family written by one of the descendants includes a photo of Charlotte at a writing desk, holding a pen.

According to various family history records, born in 1830 in Foots Cray, Kent, Charlotte Elizabeth Mead, one of about seven siblings, was daughter of John Mead, a blacksmith; her mother’s name was Mary (born Mumford), whose ancestors were possibly well-established in the parish. By the time she was 22, in 1851, Charlotte was a servant for a family in Lambeth. Within another four years, in November 1855, far away from Kent and London, she was married and living in Crediton, but I don’t know how, where, or when she met William Dart, Edith’s father. In 1861, the couple with their first two children and William’s widowed mother Jane, were living in Fountain Court in Crediton’s High Street. By 1871, the year before Edith’s birth, the Darts with two more children had moved across the road and were living in a house called Bank Court, which I believe is now 18 High Street. Perhaps Edith, the Dart’s youngest child, was born there, the following year. By the time she was eight, in 1881, the family were living at 128 High Street (near what is now Boots).

|

| 128 High Street Crediton showing archway to Dart and Francis. |

Catherine and Alice are named along with Edith, their youngest sibling; the two other children, William, the Dart ‘s son and Frances/Fanny, middle daughter, are not named in the census; perhaps they are married or living elsewhere. William Dart, father and Head of the House is also absent but there are a couple of visitors (Robert Tule and Anne T?) and a servant called Susan Lott.

Just two years later in April 1883 a local tragedy which happened near the town must have severely affected the Dart family. William’s older brother John was killed in a terrible accident whilst out at Kenford Hookway gathering wood for the firm; rolling an elm tree to move it to a timber carriage the chain had broken and John was killed outright by the falling tree.

I'm not sure if another accident involving one of the Dart sisters was Edith herself. Bill Jerman of Crediton found that in 1899 one of the sisters out walking her dog near Crediton station narrowly escaped being trampled by a train:

Mon 2 Sept 1889 Express and Echo

Narrow escape. A serious if not fatal accident had been promptly averted by the presence of mind of Mr Banks the worthy station master at Crediton station. It appears on a Saturday afternoon Miss Dart daughter of Mr William Dart builder was at the railway station awaiting the arrival of the 4.23 from Exeter. She was accompanied by a pet dog and just as the train approached at a smart speed the dog sprang from the platform onto the wooden crossing. Miss Dart very unwisely got on the step between the platform and the line to rescue the dog. Luckily for her Mr Banks who was on the platform instantly grabbed her arm and pulled her on to the platform, the engine at that moment being only about eight yards from her. Great praise is due to Mr Banks in effecting a rescue from a serious if not fatal accident. Ladies having pet dogs should take a warning from the above.

Said to be educated at home (I’m not sure if at the end of the C19 home education was typical for young women of her middle-class status), Edith did attend at least one locally held course and a follow-up examination in 1896, when she was 24. The course in Greek Art and Social Life was held at Exeter Technical College and organised by The University of Cambridge. Edith gained a distinction (Exeter Flying Post, 1 February 1896).

At the time of the next census in 1901 (not long after the celebrations described above commemorating General Buller’s return to his hometown) the eldest and youngest daughters, Catherine and Edith were still with their parents, now both in their late sixties. William, listed as ‘Contractor’ was now 67 and Charlotte two years older; their daughters were 43 and 28. Gerald, another grandson, is also with the family and a different servant, called Anne (Sether?).

During this period of her life (perhaps before she succumbed to the restrictions caused by her heart condition), the young writer was actively involved in a variety of local enterprises. There are glimpses of her comings and goings in contemporary newspapers. In 1895, when she was 23, she may well be the ‘Miss Dart’, one of five local women who applied for the post of Assistant Nurse and/or Industrial Trainer, (Crediton Board of Guardians). In 1899, the year before the occasion I described at the opening of this piece when Crediton welcomed Redvers Buller back to Crediton, she was bridesmaid at a friends’s wedding. In 1902, not long after the class in Exeter, Edith was Treasurer of Crediton’s Packer Fund (a charity organised by the town’s Board of Guardians, who were the overseers for Crediton's Poor Law Union). I haven’t yet had opportunity to find more but I believe she may also have been active with the Crediton suffragette group, one of whose leading figures was Amy Montague, a Crediton woman of Edith's generation who must have known and may have been another of the author's friends.

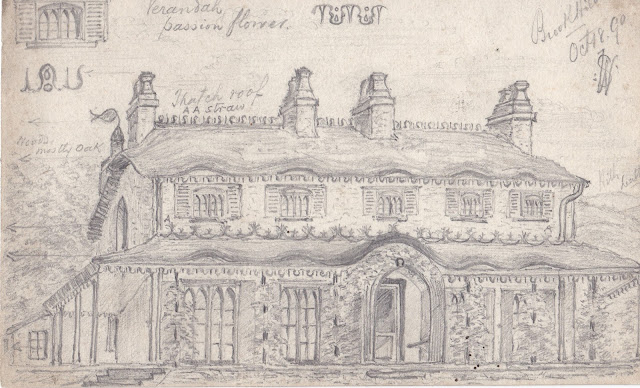

By the time of the next census, in 1911, everything had changed for the family. Most significantly, Edith’s father had died in 1904, and she, along with her widowed mother and eldest sister, who the family called Kate, had moved north of the High Street into a house called ‘The Orchard’, which I understand had been built by William for his retirement; but sadly that was not to be.

|

| The Orchard Crediton |

The Orchard is one of a row of four houses he built (sited along the bottom edge of what is now People’s Park). By now Edith was 37. There are additions to the family: a niece, Phyllis Dart aged 19 is with them, as well as a visitor called Mary Lundy and Anne (Satton?), the servant is still with the family.This may have been the house in which Edith’s niece (probably Phyllis) describes her aunt as invalid writer who was ‘exempt from all domestic or garden chores [and] seemed to spend all her time in her oak-panelled “den”, where she had quite a respectable library’.

|

| Looking down at The Orchard from People's Park in Crediton |

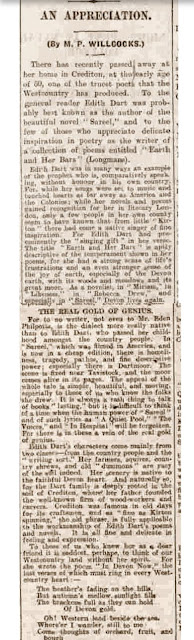

An obituary was written by Edith’s friend, MP Willcocks and published in The Western Morning News on Thursday 17th of July 1924. It is perhaps the most succinct summing up of the Crediton writer, reminding us here looking back that our past’s writers need to be kept in our local communal memory.

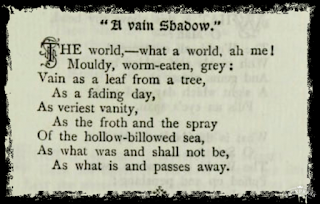

There has recently passed away at her home in Crediton at the early age of 50 one of the truest poets the Westcountry has produced. To the general reader Edith Dart was probably best known as the author of the beautiful novel Sareel, and to the few of us who appreciate delicate inspiration in poetry as the writer of a collection of poems entitled Earth and Her Bars. Edith Dart was in many ways an example of the prophet (?) who is, comparatively speaking, without honour in his own country.

For while her songs were set to music and touched hearts away as far as America, and the Colonies, while her novels and poems gained recognition for her in literary London, only a few people in her own county seem to have known that from little “Kirton” [Crediton] there had come a native singer of fine inspiration. For Edith Dart had pre-eminently the “singing gift” in her verse. The title “Earth and Her Bars” is aptly descriptive of the temperament shown in her poems, for she had a strong sense of the joy of earth, especially of the Devon earth, with its woods and meadows and its great moor. As a novelist in “Miriam,” in “Likeness,” in “Rebecca Drew,” and especially in “Sareel,” Devon lives again. (Mary Patricia Willcocks, Obituary for Edith Dart)

|

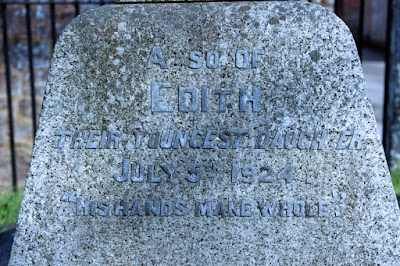

| Edith Dart's Grave in Crediton Church Cemetery |

|

| Dart family grave and memorial Crediton Church |