A – Z of Devon Women Writers & Places

|

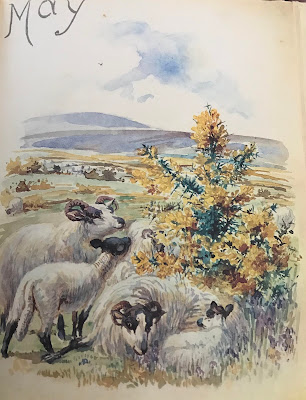

Although she is still well-known as author of the popular books The Country Diary of an Edwardian Lady and The Nature Notes of An Edwardian Lady, early C20 Diarist/Illustrator/Naturalist Edith Holden is not usually associated with Devon, or the South-West of England. Neither is she generally remembered as author. But perhaps Holden's life-journey, which included many holidays down in Devon, and her artistic achievements need to be viewed from a new perspective. Since coming across her paintings and nature journals back in the seventies, when the country's Holden fandom went crazy for her books and off-spin of Holden inspired knick-knacks and merchandise - and more especially, after I found that she had loved Dartmoor and stayed there several times during the early decades of the C20 - I've often thought of and felt drawn to her. I have already written a little about Holden in at least one earlier blog post. DoveGreyScribbles also has a lovely piece about Holden in Devon.

I believe that, challenging the default literary assessments of Holden as 'not a great literary or historical discovery … and 'an overall unremarkable woman' (see Keith Brace, 'Fragrance from the Fields of Edwardian Olton' in Birmingham Post, 18 June 1977 and Rodney Engen 'Some Diaries of Victorians and Edwardians' in Book World Advertiser 1982), Holden ought instead to be viewed as an iconic female artist, whose contributions to the field of nature writing/illustrating at the beginning of the C20 can be celebrated as formative to the recognition of the environment as a valid genre for writers. Recently academics have challenged the customary view of Edith Holden as simply artist and/or naturalist: 'she was highly politicised. Many of her animal paintings were created for the RSPCA and she marched the streets to petition against vivisection. She also supported women's suffrage'. (The Edwardian Lady; a 1970's Icon; Feminist Seventies Conference, Dr Sarah Edwards).

Given these new understandings of Holden and her work I'm going to divert away from her connections with the landscape and instead make a few observations about several other interrelated cultural concerns, the Suffrage movement and the Victorian Occult or Supernatural, both of which Holden may have been more involved with than first may appear and about which her Devon visits may provide more information. Some of the accounts about Holden leave out information about her love of and holidays spent on Dartmoor, so this is an attempt to rectify that omission. This post will not be an in depth commentary, and will probably leave more answered questions than new revelations about the Edwardian artist, but I hope just to suggest a few pointers for anyone out there who may be interested in Holden and what her life and work may have to tell us about the workings of the early suffragists and the late C19/early C20 cultural fascination with the paranormal.

It was when I found where Holden had stayed when she travelled down to Devon in the first decade of the 1900's that I became curious about her possible links with the suffragists. I'd read that she befriended the Trathens, a local family who lived at Dousland, which is a 'small settlement' just up the road from Yelverton - near Burrator and Yannadon - but given that it seems nowadays to be rather a remote location I was always rather puzzled as to why she would have stayed at Dousland in the first place. Then, in Ina Taylor's book The Edwardian Lady, I found that Holden stayed at The Grange, at Dousland, near Yelverton, which Taylor says was then an imposing boarding house that accommodated the "better class of visitor"'. The Trathens apparently lived up the road at a cottage called Belbert Cot. This property agent sale notice has pictures of The Grange and confirms that Holden stayed there. More intriguingly, one of the then leading woman of the suffragist movement, Alison Vickers Garland (who was also a playwright and novelist), apparently held classes at The Grange during the period that Holden visited Dartmoor. Julia Neville writes an account of Garland's links with the boarding house on the Devon History Website:

In the early years of the twentieth century Garland began to arrange educational-cum-holiday programmes at Dousland Grange, Walkhampton.[34] The first reference to these is that ‘a series of lectures’ was organised there, referring specifically to one given by a local cleric, Rev S. Vincent, who spoke about the life and work of King Alfred.[35] In July a three-month programme of weekly evening meetings was published under the heading of ‘Summer Holidays on Dartmoor organised by Miss Alison Garland at Dousland Grange’, with a programme including W.T. Stead, editor of The Review of Reviews, speaking on ‘Is an Anglo-American Alliance Desirable?’ and Lady Grove (secretary of the Forward Suffrage Union) on ‘The position of women in different countries’. When Grove withdrew due to bereavement Garland stepped in herself with her talk on India, as there was ‘a large house party of nearly 40 people’ to entertain.[36] There is also a reference to a programme at Dousland Grange in April 1905 when, ‘at the invitation of Miss Alison Garland’, in addition to a musical programme a dramatic sketch was performed, arranged by ‘Miss Mary Bateson BA, Fellow of Newnham College’.[37] Mary Bateson was a distinguished constitutional historian, but she was also a suffrage activist, selected as one of the speakers when the National Union of Women’s Suffrage Societies (NUWSS) met Prime Minister Sir Henry Campbell-Bannerman in May 1906.[38] It is likely that it was their shared interest in the suffrage movement that prompted this event. Garland was increasingly involved with the movement in London: she appeared at the NUWSS demonstration in Trafalgar Square in July 1910 speaking both on the West Steps for the Women’s Liberal Federation and on the East Steps for Temperance Women. (Alison Garland)

Edith Holden makes entries for April 1905 from Dousland, so she may well have been staying at The Grange when the event noted above took place. Perhaps indeed her visit there in the beginning was instigated by her previous links with Garland; I can't help but wonder if they knew each other or/and perhaps Holden knew Mary Bateson. Somewhere out there in the archives there may be some letters which would show such a connection, but as yet I have not had any chance to locate Holden's correspondence, except in Ina Taylor's biography (see above), which includes reference to Holder's letters to the Trathen family. The biography written by Neville also informs us that Garland was, like Holden, an artist so the two women may have met and become acquainted through their shared artistic interests:

As well as her music, Alison Garland was interested in art and in literature. She attended classes at the Plymouth School of Art, and exhibited at the annual student show in 1883 when, of the 350 contributors, two works of hers ‘Wonderland’ and ‘Luff Boy’ were singled out for mention.[7] The School of Art prepared students under a national course of instruction devised at the South Kensington Museum (now the Victoria and Albert Museum) and Garland made her way through the seventeen parts of which it was composed so that, although she was already teaching art at The Hoe Grammar School in 1887, she was finally able to advertise herself as holding ‘full certificate, South Kensington’ in 1888.[8] She had also negotiated with Miss Hutchens of the Stoke School for Girls that her classes would be open to pupils not attending the school. (Devon History Society)

Also, apparently, in 1912, Garland organised a 'Suffrage Summer School' on Dartmoor, which was held at another boarding-house in Dousland, called Heather Torr - which may be the Heatherside Care Home. By then Edith Holden had married sculptor Alfred Ernest Smith and was settled in Chelsea, so was probably not likely to have been down in Devon. I'm not sure whether many researchers in the UK have considered or/and written about the possibility of links between the suffragists and spiritualists in the work and writings of C19 women. I keep meaning to read the book Divine Feminine: Theosophy and Feminism in England, by Joy Dixon, which is 'a full-length study of the relationship between alternative or esoteric spirituality and the feminist movement in England', because it will probably provide valuable contextual information. In the US some writers, such as Flora Macdonald Merill, who was the same age as Edith Holden, were both spiritualists and feminists. Apparently in the States at the time it was not unusual for Mediums and Psychics to become spokespeople for the suffrage movement... Interestingly, the Holden family draw together both of these concerns. For a postmodern readership the most extraordinary manifestation of the family's involvements in what many now would label 'jiggery-pokery', was the compilation and publication in 1913 by the Holden sisters with their father of The Edwardian Afterlife of Emma Holden, a collection of messages from their mother from the 'spirit world' beyond the grave. (See the review of a recently re-published version of this text) in PsyPioneer). Could Edith Holden have been attracted down to Devon because of some now forgotten link with the C19 Victorian Occult/Victorian Supernatural? I'm afraid at the time of writing I don't have any startling discoveries to relate to confirm this; but when I look at Holden's extended family and ancestry, then reach out to take in the wide ranging circle of her social and artistic network, it seems likely that amongst them all there were individuals who had links with Devon, maybe indeed with the Dartmoor area near Dousland where Holden spent many holidays. It is hard to find out about some of the people concerned, needing time for hours of archival study which I don't have at present. So I'll have to make do with one or two thoughts. Edith's father Arthur Holden's family came from Bristol and so did Emma Wearing, her mother. The couple met and married there before moving to Birmingham where they made their home. I haven't had a chance to research their respective families, but wonder if we could trace the Holden and Wearing family lines further back we might find that at least one of their families had direct connections with Devon - possibly through either Edith's father's (Holden) or mother's (Wearing) maternal ancestry.

During the last decades of the C19 Devon became important in terms of various manifestations of what some have called the 'Victorian spiritualist crusade' (See Who Ya Gonna Call (Dr James Gregory) in the southwest of England. From the 1870's onwards there were various spiritualist associations in Plymouth and Exeter and according to Gregory several women became prominent mediums, including Sarah Martin Chapman and Miss Bond of Stoke. In 1878, The Spiritualist noted that 'We possess information that [Spiritualism] has taken root in at least six Devonshire towns, and that in one of them mediums are multiplying' (See Who Ya Gonna Call).

It is perhaps of interest that one of Devon's most notorious C18 radical woman 'prophets'/'spiritualists' Joanna Southcott, had connections with both Bristol and Birmingham, the main places with which the Holden family were associated. The St Lawrence Street Chapel, in Birmingham was apparently originally a chapel for Southcott's followers before being taken over by other sects, including the Unitarians (See Radical Spirits), a non conformist sect which became the mainstay church for the Holden family. Also, the famous Sealed Box containing Southcott's predictions was kept at the rectory of the eccentric vicar Thomas Foley, at Stourbridge, a parish not far from where the Holdens lived, at King's Norton, then Moseley; in 1803 Southcott had lived at Stourbridge for a while. Whilst there are no obvious links between any of these facts (and Southcott was from an earlier generation), given the Holden's very radical views and in particular affiliations with dissenting religious groups, they may well have known about the legacy of the controversial female prophetess from Devon.

Some years later, there was another equally eccentric Devon author, Beatrice Chase, who was just a couple of years younger than Edith Holden who coincidentally first travelled down to Dartmoor from her London home in 1901, just one year before (according to Taylor) Holden first travelled down to the moor. Chase's religious fervour and various writings often had an esoteric leaning and were frequently reviewed in spiritualist magazines such as Occult Review. (See iasop website). It's probably unlikely that the two women knew about one another because the years that Holden spent her holiday on the moor were before Chase became well-known through her writings and celebrated 'White Knights Crusade'. However, several of Chase's early writing are reviewed in contemporary occult magazines (See iasop), so perhaps Holden was familiar with Dartmoor's 'Lady of the Moor'.

… So, although I don't have any startling revelations to set down here, it seems to me that Edith Holden, woman, diarist, artist, naturalist, was much more than the solitary woman as depicted in her own now iconic nature books and Ina Taylor's biography. Perhaps indeed the somewhat sentimental quality of Holden's journal art-books detracts from and hides another layer of the artist's identity. Certainly, her life and family network link her into a far wider social, cultural and literary community than first meets the eye. And those lost Devon links may eventually help to fill in a few gaps and show up more about Holden as one of those woman who - though ostensibly on the periphery of the suffrage movement, and only 'writer' on the margins (the superimposed 'edgelands' of/on her own artwork) - was actually more actively and centrally involved in several important contemporary societal and spiritual movements.

As I reach into unknown spaces, to try and find a flicker of Edith Holden's unknown past it's as though, whilst possibly floundering in the dark, I'm echoing her own foremothers' ancestral familial 'psychic' obsessions - a kind of medium, 'channelling' for voices of the past as she/they ride the loops of time. (Read about the Victorian fascination with the supernatural on the British Library website). I hope that I, or someone else out there, will hear her/them whispering, revealing a new air-born 'automatic' text, that we can write down and can add to the intertextual layers of texts written by and about the women writers of this period - especially, for my own specialism, women-who-wrote who had Devon connections. |

See also From the Devon Ridge Where a Book Began