|

| Churchyard at Salcombe Regis Church |

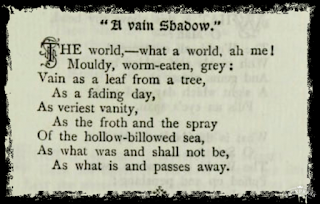

The first page of Madeleine de Lancey's

A Week at Waterloo

Lady de Lancey’s visit to Devon was short-lived as she'd been taken to the village to convalesce, after giving birth to a third child after her second marriage, but had sadly and poignantly died, on 12th July 1822, at the age of 28. The burial entry in Salcombe Regis registers states that Magdalene was 'Wife of Captain Harvey - formerly the widow of St William Howe de Lancey Quarter Master General of the Army under the Duke of Wellington'. As yet I've not been able to locate her grave in the churchyard at Salcombe Regis, although in principle I have had information which should help to find it (See the previous Lancey post). But the church and village is still an idyllic place to have an excuse to visit, so perhaps others out there will follow the quest to Madeleine De Lancey's Salcombe Regis grave.

It is important to commemorate Madeleine's connection with Devon because of the one text that she wrote seven years before, A Week in Waterloo in 1815 , a personal diary/account of her own experience nursing her first husband following the Battle of Waterloo. The text can be read at The Project Gutenberg. The opening of the narrative can be seen in the photo next to this.

Since I last researched Madeleine's life I've found that she was the sister of the writer Basil Hall a noted author on the subject of early American travel and that it was through him that she met her first husband. William Howe de Lancey. A Week at Waterloo was also apparently written at Hall's request and the introductory material to the narrative tells us that Sir Walter Scott and Charles Dickens were both impressed by it. Did De Lancey's account influence Scott's own poem of the same name? That's a question I can't answer but it seems that Madelaine herself must have impressed him as she was said to be a model for a character in in novel The Bride of Lammermoor. There's an interesting comment on the diary and the fate of the de Lancey couple and the response of these other writers on this All Saints' Church Belgium website:In 1816, “Lady DeLancey’s Narrative,” an edited version of her diary, was published and stayed in print until 1906. The tragic tale of the beautiful, doomed newlyweds, set amidst the carnage of Waterloo, became one of the 19th century’s most compelling and iconic love stories. Charles Dickens sobbed when he read Magdalen’s story 5 , and Sir Walter Scott wrote not only an epic poem, “The Field of Waterloo,” but is believed to have Lady Magdalen as his inspiration for the character, “Lucy Ashton” in his 1819 novel, The Bride of Lammermoor.

The same piece also provides a poignant postscript about Madeleine and her journal.

'In 1999, in a corner of an attic, Lady Magdalene’s great, great, great grandson made a startling discovery. Inside a dust-covered trunk, he found the widowed bride’s original diary, two portraits of young Magdalen and forty hand-signed letters.'

Crocuses in graveyard at Salcombe Regis Church photo JES

Evidently there is more to be discovered about Madeleine, both concerning her brief stay in Devon in the context of her second marriage and with respect to her literary links and its wider inter-textualities. Something to muse on for later research, for me, or perhaps someone else out there ...

****

|

| 'A Vain Shadow' Christina Rossetti |

135 years ago, during the winter of 1887, poet Christina Rossetti left London in search of the sun in Devon's Torbay. As I begin to write this piece shortly after the Christmas celebrations, with carols still ringing at the back of my mind, I can't put aside Rossetti's most famous - and now iconic - lyric In the Bleak Mid-Winter (which she wrote and published before this period). Our present day worries about how to heat our winter/wintry homes with increasing fuel bills is probably nothing when compared to the problems that people in her time must have had to endure. I wonder how much of that poem came directly from the poet's response to the cold living conditions of her time.

I wrote about Rossetti's stay in Devon in the context of the poet's life in the Scrapblog post Poets in Winter so won't repeat that here. Unfortunately for Rossetti Torbay that winter turned out to be cold and chilly and to top this inclement weather an earthquake shook the Riviera where her brother was staying whilst she was in Devon, which may have increased her anxiety about being away from her London home.

The image of one of the writers letters, alongside this, taken from the biography Christina Rossetti by Lona Packer, tells us a little about Rossetti's experience of Torquay. |

| Abbey Road looking in the opposite direction from the junction with Tor Church Road, beside the Central Church. On the right is Waldon Hill. This photo is copyrighted but also licensed for further reuse. |

I've not had a chance to find Abbey Road yet but I imagine the house where Rossetti stayed, in letters as 'Beechwood' might have been one of the terraced properties that appear in the photo, from Geograph:

'These devotional practices take the form of anecdote, prayer, or poem, exposing tensions between theological interpretation and devotional response that Rossetti then interweaves.' (Palgrave Encyclopedia)

|

| Images from Rossetti's Face of the Deep |

'There is a little village in North Devon, sheltered from the sea by a low range of sand-hills that stretches for miles on each side of it. The coast turns westward here, and no cliff breaks that line of billowy sand; northward and southward it goes, with the rhythmic monotony of the sea. The sand-hills are dotted with tufts of the long star-grass, where the rabbits sit; inland they are covered with fine blades bitten short by the sheep. Seaward lies the hard ribbed sand, glistening with salt, and fringed with the white surf of the Atlantic'. (From Audrey Craven, by May Sinclair, first published 1897 - 125 years ago).

125 years ago, in 1897 May Sinclair - whose real name was Mary Amelia St Clair - at the time an unknown woman writer whose links with Devon are generally not known about, published her first novel, Audrey Craven. One researcher labels the book a 'New Woman' novel (See The Creator); another publisher summarises the novel thus:

'Audrey Craven 'centres on a beautiful young woman, the eponymous Audrey Craven, who has managed to cultivate an entirely undeserved reputation for originality. Rather than being unique or original she is in fact a shallow self-centred and solipsistic heroine, whose only desire is to become a great muse to a great artist or thinker.' (See Delphi Complete Works of May Sinclair).

Had you not told me it was your first novel, I should have thought it came from a hand already practised ... For the work - if you will let me say so - it is very well written, in sound, careful, often polished English, assuredly such as one does not meet with every day. Moreover, the characterisation and construction seem to be decidedly good... I hope the critics will give it the attention it deserves.

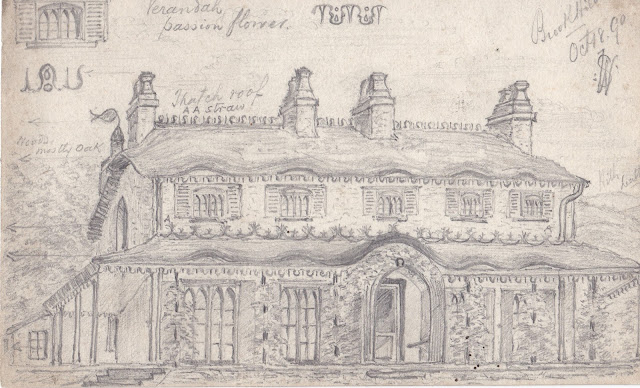

'The 1891 Census shows Mary Amelia Sinclair and her mother living at Brook Hill, Salcombe Regis (no mention of The Quest). By viewing the neighbouring houses on the Census, we believe the property was sited around the junction of Fortescue Road and Sid Road. The house may no longer exist as details of it finish around 1964. We have found another poorer but similar sketch of Brook Hill signed WS which strongly suggests that is William Sinclair, May’s brother (1851-1896)'. (See also note below)

|

| Sketch of 'Brook Hill', the house May Sinclair lived in Salcombe Regis. Drawing attributed to author's brother William Sinclair |

'He opened the door with a crash, lurched about on the broken brick flooring of the place and finally came to anchor on a cane-bottom chair.' Wings of Desire

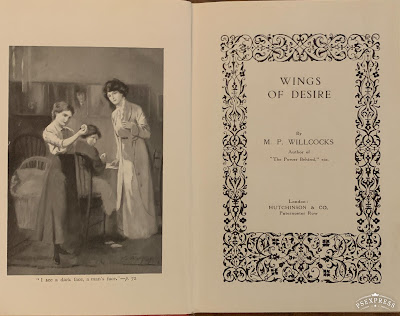

So, 110 years ago, in 1912 Wings of Desire, a novel by the important and long forgotten Devon author Mary Patricia Willcocks was published. I've written about Mary Patricia Willcocks in a previous Scrapblog post, M.P. Willcocks was a Writer from the West and mentioned how I'd found about her through the writer/journalist Bob Mann of Longmarsh Press. There's also a brief commentary about Wings of Desire in A Handful of 2021 Anniversaries, 100 years after the novel's publication.

|

| Page from M.P. Willcocks' Wings of Desire |

Although now, well into the second decade of the C21 most books are obtainable one way or other, when I first tried to find M.P. Willcocks’ novels they were not easy to get hold of. Many years out of print, they were languishing in a dusty corner of one or other basement archive, in such repositories as that of the Exeter City Library, or a local Devon town library store. I was elated when I eventually located copies of both Wings of Desire and Widdicombe - which now you can read online. I began to understand the symbiosis between landscape and literary texts in a new way. Here was a woman from my home country who wrote about the local landscape and about the types of rural Devon women who could easily have been my own foremothers. Walking through the landscape of her stories, which often figure a local Devonshire woman herself wandering through typical county territories - crossing bridges, in damp woods, under trees, or on the moor - usually very aware of and susceptible to the vistas spread before her, I found myself re-living the days of my female Devonshire ancestors.

Ranging across the spectrum of the county’s topographies Willcocks' novels offer snapshots of Devon's lost corners. Reading her novels I was reminded of Mary Webb, whose fictional writings capturing the geni-loci of her home county seem synonymous with Shropshire’s essence; Willcocks’ fiction is to Devon as Webb’s is to Shropshire. I imagine that Willcocks was influenced by her near contemporary D.H, Lawrence (though given the dates of their respective fiction publications perhaps the potential influence was the other way around); but just like Webb, who was also her contemporary, Mary Patricia Willcocks was born and spent most of her life in her home county; both women’s fiction focuses around the distinctive features of their respective home county’s landscapes. Willcocks’ work often has a backdrop of moor and sea, whilst her stories are awash with local (late C19/early C20), mostly rural characters. Preciously old-fashioned, but providing nostalgic, secure representation of an ordered world, her fiction resonates with a sense of place in which generations of ancestors lived and worked; her books are replete with what her fan Bob Mann calls ‘a mystical sense of the inseparability of past, present and future’. (Bob Mann, 'In Search of Devon's Forgotten Feminist', The Dart, June-July 1996, Number 95).

On the landing Anne paused, bright-eyed and mis-chievous. Leaning over the rail, she contemplated the hall below. It was as silent as the ancestors on the walls. Only the clattering of plates came from behind the baize-covered door that led to the older part of the house ... "Dare I?" said Anne to her sister, putting her head on one side like a bird when he raises a song to the god of raspberries. The next moment there came a slithering noise of skirts followed by a thud; Anne had slid down the ban- isters. Demurely Sara followed, wondering why Anne retained the jolly ways of a child or a man. But she knew, for Anne had been out in the world where one does things. She had not stayed at home listening to the wind in the trees, to the noise made by the footsteps of the future. It was the best thing that Sara had ever done, that sending of Anne into action. Very warm at heart, she followed the girl into the drawing-room, where Mr. Knyvett was still acting as a conduit. ' ' Harmony, ' Mr. Hereford was saying with his fingers neatly fitted in the shape of a pointed arch, "harmony is the thing we neglect in modern life. We must not jar, we must vibrate in unison. (M.P. Willcocks, Wings of Desire (John Lane, 1919). 30.

As I read the novels I kept wondering how many of my unknown Devon female foremothers were made up of the same stock as the tough and resilient female characters to which Willcocks gave voice and presence.

'Year by year we are taught, we women, to live by love—that it is our highest work. I believed it till I was shaken out of the belief. He, my lover, had his work, the thing he was made to do. He put it first before me. . . . He would not take me. There would have been fuss, lawyers, letter-writing. He would not have been left with a mind free to his task. I saw for the first time my place in the scheme of things. I am only a light woman until I can do my work.'

Sun warmed and sweet, over granite boulders where hang tufts of gorse that send golden lights across the deep brown pools, the river slips down the Enchanted Valley. Hills, grassy, patched with young bracken and scarred with grey stones, enfold it; only its swaying murmur, rising and falling like a pulse, can be heard to the summits where the sun beats down in dizzying splendour. ... Into this radiance stepped Molly and Bellew; here they sat on the rocks while the brown waters sparkled over patches of sand or gloomed across the weedy boulders (Wings of Desire, 140).

As the meeting between the couple becomes more angst-ridden, so does the description of the valley take on darker, sinister tones. A storm brews and Archer and Molly have to shelter from the moor’s dark mood:

Then she felt a physical chill fall on her and following her glance, Bellew looked up and exclaimed. Over the shoulder of the Longstone Hill, gathering across the wastes deep in on the moor, was coming a procession of clouds, inky black at the edges. The wind was shaking the trees. Low growls of thunder came from the left; it was of ill omen, thunder from the left, thought Molly. “Come,” said he, “we must hurry.” (Wings, 143).Wings of Desire’s last scenes between Sarah and Kynvett are set in an exotic fictional moorland wood, which it is not hard to identify as the real Black-a-Tor copse:

"Between large slabs of granite overgrown with moss and fern grew stunted oaks, their gnarled and knotted trunks half hidden with carpeting of whort-bushes. In the warm, scented wind the tree branches waved above the woodland gloom that was dappled with point of gold. Everywhere was light and movement, thrilling upwards from the breast of earth towards the sun’s caress .. At the head is the wild moor toward Great Kneeset with its dun stretches of ling, a mantle of brown fur, broken here and there by solitary thorn bushes white with bloom and odorous with heavy scent"(Wings).

Near the ending of Wings of /Desire

It is here that Sarah and Billy exchange their final love tryst: 'And she bowed her head for like a wonderful tree of life, their mutual trust in each other's honour bore but their love and passion as a flower'

In April 1912 The Freewoman Weekly Feminist Review carried what might be read as an ambivalent, perhaps even condescending, review of Wings of Desire, written by no other than writer Rebecca West who was - and is - one of the major writers of her time. West is somewhat critical of Willcocks' 'lack of dramatic instinct ... 'for her crisis never come cleanly and impulsively but are approached circumspectly over much unnecessary ground'. (Could there have been an element of envy/jealousy?) But West has plenty of complements for her fellow novelist. Willcocks' writing is 'strong and valuable'... 'Her novels express the passionate deliberations upon life of a wise and energetic personality ... she has an extraordinary ability for drawing characters ... they [yet] have the flush of life on their cheeks, the strength of the living in their limbs'.

West describes the character of Sarah Bellow thus:

'She has gifts as a pianist, which of course she has not been allowed to exercise after marriage—" a childless woman, with a song-bird in her heart that cannot sing, and so fettered both ways, " as her husband sentimentally observes.' (See The Freewoman)

West concludes her review of Wings of Desire thus:

"In the panoply of our newly-found emancipation we women are as serious as a little girl in a new pelisse : we dare not unbend in so much as a smile. Perhaps that is why Miss Willcocks, having written a rattling good yarn about a reckless buccaneer of to-day who leads some fine gentlemen across the tumbling; tropic seas to the black snow-capped cliffs and yellow coves of South America in search of phantom gold, felt shy about publishing such a frivolous production, and weaved it into "Wing s of Desire " with the slenderest thread. It adds the last touch of riotous confusion to a book that almost faints under the weight of its own luxuriance. But what a magnificent fault!" (See The Freewoman)

My dear, go to your room. This is not right, You are acting in defiance of my known wishes, although, no doubt, thoughtlessly. Bid your sister goodnight and go.”

Val did not even wait to carry out the first half of the Canon’s injunction. She caught up her brush and comb and left the room. (The Optimist - Great War Fiction Plus)

|

| Croyle House across the field |

'I'm afraid I found this very hard going. It just didn't hold my attention, I felt unable to make a connection with any of the characters, and I had to struggle to make it to the end. I do enjoy Delafields books and I feel she was a really talented author, but this was a disappointment to me'. Amazonreview

Yet another reviewer is extremely complimentary about The Optimist judging it to be 'one of the most thought-provoking novels of the 1920s'; this review concludes that 'It [The Optimist] deserves a reprint'. I hope to make up my own mind about he novel one day, and will be especially keen to note the intertextual links between The Optimist and Jane Austen.

Here, in the accompanying image, is a copy of one contemporary review which mentions The Vision of Desire - a 'good honest romance'. Another book-jacket reviewer calls the novel ' an absorbing romance written with all that sense of feminine tenderness that has given the novels of Margaret Pedler their universal appeal'. (Grosset & Dunlap publishers New York).

****

And now, bringing this celebratory Devon chronology a little closer to us chronologically, and, for now, closing it - another novel by Margaret Pedler,80 years ago, in 1942, another of then acclaimed and popular romance novelist Margaret Pedler's novels, Then Came the Test was published.

Annoyingly thus far a perfunctory search on google has only provided a brief synopsis of that novel. It summarises that plot:'An English story of the extravagant Sherwoods, geared to horse and hounds, and coming up against sober reality when debt loses them their estate, and war breaks out. Familiar enough triangle pattern, with tribulation getting its tribute, and love eventually winning out'. (Kirkus)

Yes, fair enough there are several copies of the novel - including a scattering of first editions - available on sites such as AbeBooks, but they are few and far between and not cheap. I hope I'll return with more commentary about this long lost novel as soon as opportunity arises...

Note: Re update following the sketch above of the cottage where the Sinclair family lived. I am very grateful to Jan Wood, archivist at Devon Heritage Centre who kindly assisted in helping to locate the house. Here is part of the email she sent providing details about the whereabouts of the property. '... named as Brookhill - on the 2nd edition Ordnance Survey map [dated to the early 1900s] on the Know Your Place website. It is in Grigg's Lane, which ran at the time from the junction of Sid Road with Fortescue Road (this area is now called Sidford) towards the east, in the direction of Salcombe Regis village. Just past Brookhill/Quest, close to Thornhill Plantation, and before reaching Salcombe Regis village, Grigg's Lane seems to have turned at that time into a narrower track or pathway. Brookhill stood on the south side of the lane towards the village. .. I have just found it on the 2019 basemap as well, named as Quest - so it may still be the same house - if it is not a rebuilt house with the old name still kept. The lane still turns into a trackway just past the house'.

Well there you have it, another year and a selection of the past's celebrated Devon women writers and texts. I hope I'll be here next year to catch up on some more literary anniversaries!