Part 3; White Rose and Golden Broom

'He was taken to Taunton and accompanied the king as a prisoner on the triumphal march to Exeter where the monarch was welcomed with jubilation…Perkin's wife Katherine was fetched from St Michael's Mount. The king took a shine to her, and she was accepted into his court under the wing of the queen and eventually remarried. While she was in Exeter, Perkin was humiliated by being forced to repeat his confession in front of her …' (Devon Perspectives).

'Perkin Warbeck, another pretender to Henry VII’s throne, was given a similar Tudor spin – an odd name, humble background, documented torture, beatings to the face – to paper over the strong possibility, backed by crowned heads across Europe, that he was the genuine Richard, Duke of York (the youngest of the princes in the Tower).' (British Heritage)

|

| Cast of White Rose & Golden Broom |

C20 Coldridge links; Beatrix Cresswell ‘s Pageant

‘It is a spell! A spell! That I have drawn from Classenwell’ (From White Rose and Golden Broom)Although along the various paths of my research I’d noticed that White Rose and Golden Broom; a Drama of Exeter, a pageant written by Devon author Beatrix F Cresswell had been performed on 15th June 1910 in the Palace Gardens of Exeter Cathedral, I didn’t really expect to go out of my way to get a copy of the text.

Exeter Cathedral from the east

cc-by-sa/2.0 - © David Smith -

geograph.org.uk/p/3539908

So thanks to my local and still open branch of West Somerset Libraries I ordered a copy of the pageant via Inter library loans. I waited its arrival eagerly…

… We know that Beatrix Cresswell visited and wrote about Coldridge Church. Several of the ‘John Evans is Edward V researchers’ mention her as ‘expert’ in her identification of the stained glass picture at the Chancel Chantry as an authentic portrait of the young king – (though her expertise is I note taken for granted rather than esteemed)! They mention that Cresswell connected Coldridge with Cecily Bonville (See end of Part Two). They also say that Cresswell confirmed that the portrait on the stained glass is of Edward V: ‘The early 16th century stained glass portrait of Edward V. Confirmed by expert Beatrix Cresswell to be genuine’. (See MedievalPotPorri). Cresswell’s expertise is frequently called up in descriptions of Coldridge church and (though as yet I’ve not been able to read her notes first hand) it seems that she was one of the first Devon historians to express puzzlement about its singular features:

And another says

You may notice a discrepancy in these commentators’ attribution of the year of Cresswell’s own visit to Coldridge; one casually refers to the early 1920s, whilst the latter one above specifies 1905. Why does this matter? Well, after White Rose and Golden Broom arrived from the library airwaves and I began browsing through to get the gist of the text I kept wondering if Beatrix Cresswell had been impelled to write the drama because of her curiosity following her trip to the church.

For Cresswell’s pageant may also have been influenced by earlier literary texts. Devon’s C17 dramatist John Ford had written a play titled Perkin Warbeck, then more recently Mary Shelley’s novel The Fortunes of Perkin Warbeck; a Romance, published in 1830, had re-imagined the events around Perkin Warbeck’s rebellion. Most importantly Shelley’s initial premise was that Perkin the impostor was actually and really Richard of Shrewsbury, Duke of York - younger brother of Edward V and the other lost prince - an opinion that recent researchers into the Coldridge mystery are very much in tune with.

The eventual resolution, the clearing up of confusions and play’s conclusion – when Catherine is reunited with Edmund – indicate a degree of historical revisionism on the part of the author. I read the play's ending as suggesting that Edmund the son-found-again, as heir of Catherine’s disgraced husband, last of the Plantagenet line, is not son of an impostor, but as descendant of Richard Duke of York, is progenitor of a renewed Plantagenet line. Catherine's belief in her husband's true status as the real deal is prefigured at the beginning of the play when she explains to her servant Alice that

and at the play's conclusion, when both the Priest and Matthew, now accepting of the couple's 'new', son, apparently reassure Catherine on her sudden change of mind and consequent outburst of doubt about Edmund's ancestry: 'since branch and flower of Royal Plantagenet/are dead and withered like this withered broom'. The priest consoles her:

cc-by-sa/2.0 - © David Smith -

geograph.org.uk/p/3539908

In this day and age, when on demand we can get our fill of historical fix through media streaming, this play's title didn’t sound too enticing. I knew that the pageant's subject was Katherine/Catherine Gordon, sometime wife of infamous impostor Perkin Warbeck, but she I'd believed to be an inconsequential medieval lady who I’d not ever thought of as being of great interest to us Devon folk. Yes, I was curious, but from what I knew of her assumed many other of Cresswell’s texts would be more significant than the script of a probably minor pageant; White Rose and Golden Broom sounded an obscure drama. But after visiting Coldridge church and stumbling upon the information about the medieval mystery that may be held within the hidden capillaries of the building's stones and ancient wood, I soon changed my mind. Anyone involved in the Devon network of familial or social networks focused around the puzzle of the lost princes is worthy of scrutiny and, as its subject was widow of one of those who’d impersonated the younger of the princes, a text featuring Katherine/Catherine Gordon deserved at least a look in. What take did Beatrix Cresswell have on that lady – about who until now the only fact at my fingertips was that reputedly she was one of the most beautiful women of her age?

So thanks to my local and still open branch of West Somerset Libraries I ordered a copy of the pageant via Inter library loans. I waited its arrival eagerly…

… We know that Beatrix Cresswell visited and wrote about Coldridge Church. Several of the ‘John Evans is Edward V researchers’ mention her as ‘expert’ in her identification of the stained glass picture at the Chancel Chantry as an authentic portrait of the young king – (though her expertise is I note taken for granted rather than esteemed)! They mention that Cresswell connected Coldridge with Cecily Bonville (See end of Part Two). They also say that Cresswell confirmed that the portrait on the stained glass is of Edward V: ‘The early 16th century stained glass portrait of Edward V. Confirmed by expert Beatrix Cresswell to be genuine’. (See MedievalPotPorri). Cresswell’s expertise is frequently called up in descriptions of Coldridge church and (though as yet I’ve not been able to read her notes first hand) it seems that she was one of the first Devon historians to express puzzlement about its singular features:

‘Early in the 1920’s, the notable church historian, Beatrix Cresswell, puzzled why the isolated village of Coldridge had such a significant church and also why it contained one of the very few stained glass portraits of Edward V, one of the Missing Princes in the Tower. For students of the Wars of the Roses, St Matthew’s should not be missed!’ (Visit MidDevon)

The same commentator notes that:

'As far back as the writings of Beatrix Cresswell in the early 1900’s, learned authors have been puzzled by the rare stained glass window of Edward V in the Evans Chantry at Coldridge Church, Devon, one of only four contemporary depictions of him in glass’. (A Portrait of Edward V)

'We have a wonderful hand written account of the church by Beatrix Cresswell around 1905 when she comments: "The church is built on a plateau and around it gather the few cottages of which the village now consists … In former times it may have been of greater importance. Nothing now remains to explain why this distant, and somewhat dreary spot (!!) should have so fine a church'. (I’ve mislaid the source of this quote, will insert when located again).

You may notice a discrepancy in these commentators’ attribution of the year of Cresswell’s own visit to Coldridge; one casually refers to the early 1920s, whilst the latter one above specifies 1905. Why does this matter? Well, after White Rose and Golden Broom arrived from the library airwaves and I began browsing through to get the gist of the text I kept wondering if Beatrix Cresswell had been impelled to write the drama because of her curiosity following her trip to the church.

|

| Start of Introduction of White Rose and Golden Broom |

In light of the play’s conclusion, in which Cresswell apparently envisages a future in which England is peopled by an ‘offshoot of Plantagenet’, implying an eventual unbroken Royal line of Plantagenet monarchs, I am tempted to think she may have been inspired to write her play after seeing first hand the stained glass with the rare portrait of Edward V and the other unique church features which are discussed by those who write about the Coldridge mystery (see Medieval PotPourri). However, until I’ve had a chance to see first hand when the writer visited Coldridge, and if the play was first drafted shortly afterwards it is only a hunch on my part.

For Cresswell’s pageant may also have been influenced by earlier literary texts. Devon’s C17 dramatist John Ford had written a play titled Perkin Warbeck, then more recently Mary Shelley’s novel The Fortunes of Perkin Warbeck; a Romance, published in 1830, had re-imagined the events around Perkin Warbeck’s rebellion. Most importantly Shelley’s initial premise was that Perkin the impostor was actually and really Richard of Shrewsbury, Duke of York - younger brother of Edward V and the other lost prince - an opinion that recent researchers into the Coldridge mystery are very much in tune with.

'It is not singular that I should entertain a belief that Perkin was, in reality, the lost Duke of York ... no person who has at all studied the subject but arrives at the same conclusion.' Mary Shelley, See Preface to Perkin Warbeck).

(There is much current debate as to whether P/Richard made a brief diversion en route to Exeter to meet up with his elder brother Edward, alias John Evans at or near Coldridge - (eg See Medieval PotPourri). But no, I have not yet read Shelley’s Warbeck novel, though given the complementary reviews it attracts I hope to find time and space to do so one day. (See for example 'The politics of ambivalence: romance, history, and gender in Mary W. Shelley's Fortunes of Perkin Warbeck').

A very quick browse of and around Fortunes is enough to tell me that the novel is not superficial in its re-imagining of Perkin Warbeck as Richard of Shrewsbury, Duke of York, for Shelley obviously immersed herself in her subject; The Fortunes of Perkin Warbeck has a formidable cast of characters and comes with an incredibly impressive understanding of all political, social, historical and genealogical repercussions pertaining to the events of that rebellion. Was Beatrix Cresswell familiar with Shelley’s fictional version of Perkin Warbeck? Perhaps it was the determined argument of the novel that persuaded the Devon author to give credence to the theory that Warbeck was Richard of Shrewsbury and not impostor.

Cresswell’s work certainly suggests she was as equally determined as Mary Shelley to investigate relevant historical sources. Although she doesn’t mention Shelley’s novel in her Introduction to White Rose and Golden Broom, the author specifically refers to one or two other literary predecessors whose texts had influenced her understanding of her drama’s background, the chronicler/poet Bernard of Toulouse (Bernard Andre) and Miss Strickland (Agnes Strickland) - both of whom had commented on the events which had led to Katherine /Catherine’s arrival in Exeter at the same time as her husband. Toulouse described how Henry VII had ‘summoned Catherine from Cornwall, confronted her with her husband and forced Perkin to confess his imposture to her ..’. Miss Strickland had written that ‘Catherine was very much attached to Warbeck and [perhaps a crucial observation for Cresswell] certainly at the time of her marriage she believed him to be Richard Duke of York’ (see Lives). In her Introduction Cresswell also explains the play’s real links with Exeter’s past. However, notwithstanding her acknowledgment of her pageant’s historical backdrop and its background sources Cresswell says that her own take on the drama is ‘wholly fictitious.’. She adds that

Cresswell’s work certainly suggests she was as equally determined as Mary Shelley to investigate relevant historical sources. Although she doesn’t mention Shelley’s novel in her Introduction to White Rose and Golden Broom, the author specifically refers to one or two other literary predecessors whose texts had influenced her understanding of her drama’s background, the chronicler/poet Bernard of Toulouse (Bernard Andre) and Miss Strickland (Agnes Strickland) - both of whom had commented on the events which had led to Katherine /Catherine’s arrival in Exeter at the same time as her husband. Toulouse described how Henry VII had ‘summoned Catherine from Cornwall, confronted her with her husband and forced Perkin to confess his imposture to her ..’. Miss Strickland had written that ‘Catherine was very much attached to Warbeck and [perhaps a crucial observation for Cresswell] certainly at the time of her marriage she believed him to be Richard Duke of York’ (see Lives). In her Introduction Cresswell also explains the play’s real links with Exeter’s past. However, notwithstanding her acknowledgment of her pageant’s historical backdrop and its background sources Cresswell says that her own take on the drama is ‘wholly fictitious.’. She adds that

Not all of the plot of the pageant is fiction however. It is often quoted that Catherine Gordon did have a son with her husband Perkin Warbeck; the child was born in 1496; and according to some sources another baby was born, but didn’t survive. Similarly, sources suggest that when Perkin Warbeck left Cornwall to prepare for battle the son was left with his mother on St Michael’s Mount, and therefore must have been with her when she arrived in Exeter. However, in another version, an alternative account of the rebellion, Catherine had a miscarriage. Anyway, whatever the ‘truth’ about a real son, in the reinvented pageant version by Cresswell Catherine has recently born a son, it’s implied his birth was shortly before her arrival in Exeter:

'[her story] represents Catherine Gordon returning to Exeter some years after Warbeck’s death, to look for a child, his son and heir, abandoned in the city when she was brought here by Henry VII'. (See White Rose and Golden Broom, available through Devon Library Services)

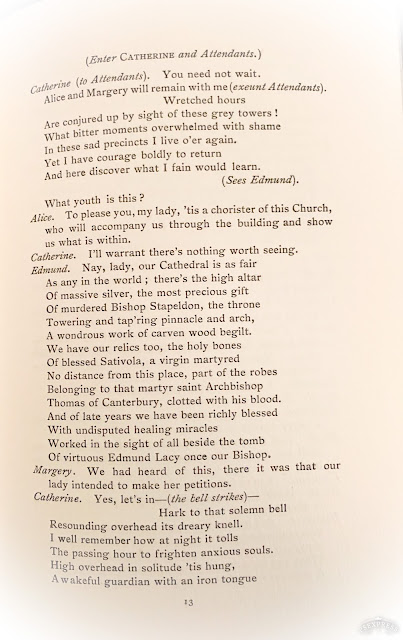

‘Scarce twice seven days had shone upon his life,/before by Henry’s order I arrived/in this sad city … my babe, son of the hapless youth/called Perkin Warbeck – Richard Duke of York …' (From White Rose and Golden Broom)In Cresswell’s pageant the plot’s development is construed around the device of ‘crossing wires’, a mix-up between two key characters, which inevitably resolves at the final denouement. Catherine’s return to Exeter with her second husband to find her once deserted child is mirrored by the intent of her husband Sir Matthew Cradock, who has accompanied his wife on her visit, but with an ulterior motive; ‘I have come to Exeter on matters of my own’ … he informs Amyas Bampfield, adding that Catherine has ‘taken our childless state most grievously to heart’ and that ‘since my wife is so set upon finding an heir’ [they have come to Exeter] ‘to supplicate at the holy shrines here for an heir’. However, Sir Matthew's intent is to ‘find an heir this very day’. He is looking for a son, an heir, a child he can ‘adopt’, to take the place of their non-existent son; she is seeking to reunite with the real son she left behind in Devon. Inevitably, in their corresponding search, both husband and wife settle upon the same boy – Edmund, a ‘foundling without fortune’, who has been brought up as chorister at the cathedral.

The eventual resolution, the clearing up of confusions and play’s conclusion – when Catherine is reunited with Edmund – indicate a degree of historical revisionism on the part of the author. I read the play's ending as suggesting that Edmund the son-found-again, as heir of Catherine’s disgraced husband, last of the Plantagenet line, is not son of an impostor, but as descendant of Richard Duke of York, is progenitor of a renewed Plantagenet line. Catherine's belief in her husband's true status as the real deal is prefigured at the beginning of the play when she explains to her servant Alice that

'though my ill-starred husband had confessed

A base imposture it may be that threats

Of torture wrung from him the sordid tale.

His death was fore-determined, sentence passed.

It little matters unto dying men

Under what name they die sure their true names are writ Heaven.'

and at the play's conclusion, when both the Priest and Matthew, now accepting of the couple's 'new', son, apparently reassure Catherine on her sudden change of mind and consequent outburst of doubt about Edmund's ancestry: 'since branch and flower of Royal Plantagenet/are dead and withered like this withered broom'. The priest consoles her:

Lady, not so, thou know'st plantagenistais evergreen, and does not fade away.But since the day that Geoffrey of AnjouFirst pluckt and wore it in humilityIt grew and flourished till in toppling prideThis weakling stood supporter of a throne.Though now no longer it may wreathe a crown.Yet I declare that as this golden flowerStill gleams in beauty on the withered stem,So shall the Royal name PlantagenetIn England ever be an honoured nameSince what is great and noble cannot die.

and Matthew adds

'Tis so, the world in future times shall seeIn days to come, no ancient house shall standBut that from sire to sire is reckoned backTo some ancestral off-shoot of Plantagenet.And far and wide in continents unknownWhere English feet shall tread and English tonguesShall break the silences of virgin woods,The English people peopl'ing half the worldBuilding new homes 'neath unfamiliar stars,Though men of English race to Britain's skiesUnknown, shall yet know this, and make a boastOf their descent from Royal Plantagenet.

Devon Canon/s

Whatever its take on the repercussions arising from the real-life drama of Perkin Warbeck in Exeter in the C15 I believe that, just as many other long-forgotten or and now sidelined texts by women linked with the county of Devon, Beatrix Cresswell’s little pageant deserves to be brought to the literary light again, reinstated as part of Devon’s literary compendium. Ok, I’m sure there’ll be people who stumble on this blog post one day for whom both author and text will come across as being obscure and utterly irrelevant in our social-media judgement driven age. They’ll quickly pass on by. But speaking from the point of view of someone (yes, me) who is often/always probably writing from the edges, living an interior life in the dreamy shadows well away from the central stage, White Rose and Golden Broom is a real find. Cresswell’s play is filling in gaps, reinventing a lost Devon his/her story from the perspective of a woman from the deep past whose own forgotten role in our county’s narrative journey can now be brought back from the shadows and reassessed – especially in light of this post and its links with the current preoccupation with rejigged scenarios around the events of the disappearance of the two princes. One of my themes in this post’s Part 2 has been to suggest that research into the scenario ‘John Evans may be Edward V’ at Coldridge should take into account the possibility of contemporary women (many of whom lived within reach of Coldridge) having an active role in events, or at least providing us with the chance to scrutinise their genealogical charts to suss out more hidden connections between individuals of the time who may have been involved.

The ‘heroine’ woman in question in the pageant, the play’s main character, ie Catherine Gordon, is someone not considered particularly central to Devon’s history. As such she, outlying Devon female from her-story, stands for many women who have popped in and out of focus through the centuries, whose journeys through their landscape and times have been more or less erased from historical consciousness - except for traces of names on old documents such as genealogical charts and/or old records of land transactions etc. We can only readmit the hidden women into a viable chronology through imaginative reconstruction, out of the box thinking, which usually takes some kind of research into those who circled around their lives so as to intuit into the blanks where they still roam around in the shadowed corners.

Whatever its take on the repercussions arising from the real-life drama of Perkin Warbeck in Exeter in the C15 I believe that, just as many other long-forgotten or and now sidelined texts by women linked with the county of Devon, Beatrix Cresswell’s little pageant deserves to be brought to the literary light again, reinstated as part of Devon’s literary compendium. Ok, I’m sure there’ll be people who stumble on this blog post one day for whom both author and text will come across as being obscure and utterly irrelevant in our social-media judgement driven age. They’ll quickly pass on by. But speaking from the point of view of someone (yes, me) who is often/always probably writing from the edges, living an interior life in the dreamy shadows well away from the central stage, White Rose and Golden Broom is a real find. Cresswell’s play is filling in gaps, reinventing a lost Devon his/her story from the perspective of a woman from the deep past whose own forgotten role in our county’s narrative journey can now be brought back from the shadows and reassessed – especially in light of this post and its links with the current preoccupation with rejigged scenarios around the events of the disappearance of the two princes. One of my themes in this post’s Part 2 has been to suggest that research into the scenario ‘John Evans may be Edward V’ at Coldridge should take into account the possibility of contemporary women (many of whom lived within reach of Coldridge) having an active role in events, or at least providing us with the chance to scrutinise their genealogical charts to suss out more hidden connections between individuals of the time who may have been involved.

The ‘heroine’ woman in question in the pageant, the play’s main character, ie Catherine Gordon, is someone not considered particularly central to Devon’s history. As such she, outlying Devon female from her-story, stands for many women who have popped in and out of focus through the centuries, whose journeys through their landscape and times have been more or less erased from historical consciousness - except for traces of names on old documents such as genealogical charts and/or old records of land transactions etc. We can only readmit the hidden women into a viable chronology through imaginative reconstruction, out of the box thinking, which usually takes some kind of research into those who circled around their lives so as to intuit into the blanks where they still roam around in the shadowed corners.

|

| Catherine Gordon enters the pageant. |

Apparently obscure dramatic scripts such as White Rose and Golden Broom may not read as important stand alone texts, but they are noteworthy as literary samples written by women in and about their local landscapes (topographical and historical, metaphorical) where the texts rejig the accepted and default narrative journey of a community’s past. As such, they are literary gold dust.

Pageant tradition

Pageant tradition

And Beatrix Cresswell was not the only woman from Devon to write a pageant for performance in celebration of a historical occasion. Several pageants written by other local female writers were staged by local performers during the early to mid C20. Indeed, whereas in the post-modern media driven world pageant as important literary form tends to be dismissed as of minor import, at the beginning of the C20 according to one recent source pageants in general became a popular literary trend:

Today pageants are certainly not forgotten, but they are rarely per- formed and do not attract the number of performers, organisers and spectators that they did in their heyday. It is easy, therefore, to overlook their importance in communities across the country during the twentieth century. Pageants generated considerable comment in the press, both local and national, and featured frequently in novels and plays. Moreover, they spawned a substantial culture of printed ephemera and souvenirs, including programmes and books of words, cutlery and crockery, com- memorative medals and so on.The verb ‘to padge’ or ‘to paj’, meaning to participate in a pageant, was in popular usage during the first third of the twentieth century. (See Restaging the Past; Historical Pageants, Culture and Society in Modern Britain; Edited by Angela Bartie, Linda Fleming, Mark Freeman, Alexander Hutton, and Paul Readman).

There may well be intertextual connections between some of the local Devon-authored pageants. Cresswell’s Exeter drama of 1910 certainly apparently became some kind of model for at least one other female writer. In 1932 Mary Kelly, founder of The Village Drama Society, wrote A Pitiful Queen: an Episode in the Civil War June 30 1644, which, like that of her predecessor’s is also set in Exeter. A Pitiful Queen takes as its subject another royal woman (Henrietta Maria) who visited Exeter during the Civil War and gave birth to her daughter Princess Henrietta Maria Stuart in the city. Fair enough, the apparent similarities between the two pageants may just be coincidence; Kelly may just have been conforming to the by then established pageant convention, which according to Restaging the Past ‘not infrequently blended fact and fiction … [was] always primarily concerned with the past and its representation in the present’. Also apparently key to the pageant tradition as it developed was a plot which kept in line with the facts as they were known about the history it represented:

'Many pageants insisted on faithfulness to the historical record and strove for ‘authenticity’, as far as possible, in costume, dialogue and content.’ (Restaging)

It would be fascinating to study both these pageants in terms of links between the authors' approaches and their faithfulness to historical facts. I have not yet had a chance to read the text of Kelly’s A Pitiful Queen (and to do so would be a remit beyond this blog post), but certainly (as she noted in her Introduction Cresswell’s White Rose and Golden Broom is ‘wholly fictitious’, its narrative straying quite radically from the known facts about Catherine Gordon’s links with Exeter.

However, as already noted above, for the most part White Rose and Golden Broom describes real events of Exeter’s (and its Cathedral’s) history, including representations of real local characters presented against an authentic local background which include evocations of Devon landscapes such as Dartmoor. But slightly deviating away from absolute authentic depiction of its plot’s background, the pageant merges its realism with fragments taken from folk-tale, legend and local myth. Cresswell would have been steeped in Devon’s surfeit of tales that especially swirled around its moorland landscapes. One of the pageant’s characters, ‘The Witch of Classenwell Pool’, the soothsaying ‘crooked aged crone’ who ‘shuffles across the pavement’ to stir up the action in Act 1 is a renamed ‘witch of Sheepstor’, who according to legend haunted the pool, now usually named Crazywell, which was said to be bottomless and thus source of various local lore.

|

'What crooked aged crone/shuffles across the pavement?' |

According to folk-tales the Sheepstor witch was said to give incorrect, twisted information to those who consulted her for advice. In White Rose Cresswell’s witch declares ‘I am the power that dwells at Classenwell/ … there Perkin Warbeck once/climbed arduously to learn what should befall/his future, and he read the fated words/across the mystic pool’.

As far as I’m aware there is no factual or a priori historical linking of Perkin Warbeck with either witch or pool; Cresswell’s plot is perhaps a version of traditional lore in which it is the C14 Piers Gaveston who seeks to know the future from gazing into pool’s depths.

In my imagination I like to believe that Beatrix Cresswell's creative decision to think out of the default historical box was connected to her visit to Coldridge church. In my fantasy she decided to construct a narrative whose main plot involved bringing Catherine Gordon, Perkin Warbeck’s (Richard Duke of York’s) widow back to Exeter to reunite with her baby son so as to suggest, via the symbolic association of planta genista, the broom plant, that Perkin Warbeck was the real deal, the lost prince assumed dead who’d returned to reclaim the Plantagenet royal line; a descent which therefore wasn’t stamped out, but in actuality through the imagined descent of sons from Catherine’s son onwards, is still thriving. I read Cresswell’s pageant as a recasting of our understanding of the chronology of the past, a creative strategy which she may have been inspired to use after coming upon the portrait of the lost prince Edward V at Coldridge church and pondering on its implications.

(PS apologies if not all of the sources quoted above have been attributed).

No comments:

Post a Comment

Comments welcome!